200 years have passed since the Marquis de Lafayette visited Fredericksburg, Virginia. More than 40 years after the United States won her independence from British rule, President James Monroe invited Lafayette to visit the country he had helped create as an official Guest of the Nation. Monroe wrote that Congress had passed a resolution expressing “the affectionate attachment of the whole nation to you, and of their desire to see you again among us.”1 Beginning in July 1824, Lafayette visited each of the 24 states over the course of 13 months.

His stops in each city and village were published in newspapers and followed eagerly by citizens across the country. In each place he visited, Lafayette was received with celebrations and gladness. Who was this Frenchman, and why did Americans praise and embrace him with such warmth?

Early Life

Born September 6, 1757 at the Château de Chavaniac, opens a new window in France, Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette was descended from two ancient aristocratic families. His father, a colonel in the French grenadiers, was killed in battle during the Seven Years War between France and Great Britain, when Lafayette was only two years old. He was raised at his father’s estate in Auvergne, France by his grandmother until he was 11, when he moved to Paris to live with his mother, attend school, and learn the ways of the nobility.

When Lafayette was 13 years old, his mother and his grandfather died within a few months of each other, leaving him a substantial fortune to accompany his title. Family quickly arranged for his future as an officer of the king and betrothed him to Adrienne d’Ayen de Noailles, a member of one of the richest, most powerful families in France.

In 1774, Lafayette and Adrienne were married, and they quickly became part of Louis XVI’s glittering court, attending balls, concerts, and dinners with other aristocrats. Although he was living the life of a nobleman as his mother had desired, Lafayette’s greatest desire was to be a soldier. He soon got his chance.

When he was 18, he assumed the post of Captain of the Noailles Dragoons and met the Duke of Gloucester, from whom he learned about the rising rebellion of the American colonists. While Lafayette was initially interested in avenging his father’s death and France's defeat by the British in 1763, he became increasingly committed to helping the colonists win their freedom from British rule.

He wrote, “When I first heard of [the colonists’] quarrel, my heart was enlisted, and I thought only of joining my colors to those of the revolutionaries.”2

With great enthusiasm, Lafayette bought and outfitted a ship, filled it with French soldiers who wanted to join in the fight, and got ready to set sail when word that both his father-in-law and the King of France opposed his plans. He disguised himself to avoid the king’s messengers and set sail for America.

His Role in the American Revolution

Lafayette and his men arrived in South Carolina in June 1777, made their way to Charleston and then to Philadelphia, where the Continental Congress was meeting. They arrived on July 27, 1777, and were initially turned away. Finally, Lafayette convinced Congress to let him serve in the Continental Army as an aide to George Washington without pay. Washington received him cordially, beginning a friendship that lasted the rest of their lives.

While many were skeptical about this 19-year-old Frenchman, he soon proved his bravery and commitment to the Americans in the Battle of Brandywine, where he fought with zeal, even when wounded, and did not back down although others were fleeing. As a result of his courage and skill, Congress appointed him a commander, making him the youngest general in the Continental Army.

Over the next several years, he served with distinction, and his efforts helped convince the French government to support the colonists in their fight. In October 1781, Lafayette and his troops cornered Cornwallis and the British troops at Yorktown. They were joined by Washington’s army and a fleet of French ships. Lafayette then had the honor of seeing Cornwallis surrender after ten days of bombardment by the Americans. He returned home in 1784, leaving the new country in peace.

Back in France

Lafayette’s strong beliefs in the ideals of freedom and political liberty caused him to wish the same for everyone. In 1786, he bought two sugar plantations and converted them to spice plantations, which required less labor and more humane practices. He wrote to John Adams, who also opposed slavery, “Whatever be the complexion of the enslaved, it does not, in my opinion, alter the complexion of the crime which the enslaver commits….”3 He was willing to spend his own fortune and call on friends and political allies to aid him in paving the way to emancipation and to be an example to slaveholding nations that there was a better way than slavery.

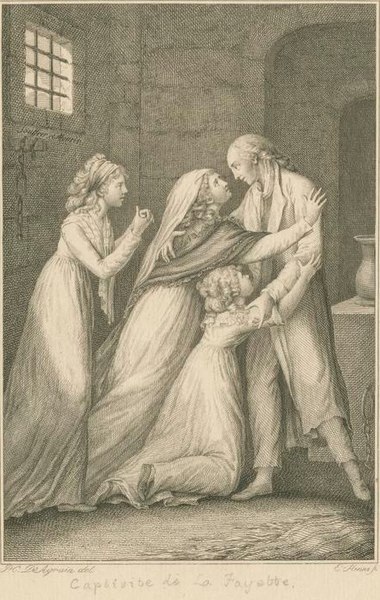

When he expressed the desire for political liberty for all people in France, both the King and the revolutionary factions who had seized power in France viewed him as a traitor. He lost his fortune, fled France, and was imprisoned for five years by France’s enemies, Prussia and Austria. His wife Adrienne, who had remained in France, was arrested and condemned to the guillotine. James Monroe, the American Minister to France, his wife Elizabeth, and other influential Americans pressured the French government to release Adrienne, and, in January 1795, French officials freed her. Lewis Littlepage, opens a new window, a Virginia native with ties to Fredericksburg, gave Adrienne a large sum of money to support her as she sought to leave France.

She immediately petitioned the Austrians to allow her and her daughters to visit Lafayette in prison. In October 1795, the family was reunited and endured imprisonment together before being allowed to move to Denmark in 1797. Lafayette finally returned to France in 1800, where he continued to fight for “freedom of thought, speech, writing, printing, and publishing.”4

Visit to Fredericksburg

On Saturday, November 20, 1824, Lafayette and his companions arrived in Fredericksburg. They were escorted through the streets by a company of youths called the “La Fayette Cadets,” a company of riflemen from Falmouth, the Rifle Company of Captain T.H. Botts, and the Washington Guards, along with the Marine Band from Washington and Fredericksburg citizens who joined the procession as it passed by.

General Lafayette was welcomed by Mayor Robert Lewis in front of the Town Hall, after which a ball in his honor was held at the Farmer’s Hotel. In response, Lafayette rejoiced “in the happy opportunity to re-visit this district”5 referring to 1781, when he stopped to visit George Washington’s mother, Mary Washington, and sister, Betty Washington Lewis. Lafayette and his entourage stayed with Mr. James Ross in his house on Caroline Street. The Fredericksburg Branch of Central Rappahannock Regional Library is located on the site where the Ross House once stood.

On Sunday, Lafayette, his son, and his secretary, Mr. LaVasseur, visited Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4,, opens a new window where he was welcomed warmly by its members. Since this Lodge was George Washington’s mother Lodge (where he was initiated), they elected Lafayette as an honorary member due to his long friendship with Washington. Afterward, he was escorted by Lodge members to St. George’s Episcopal Church for Sunday services. Lafayette spent the rest of the day visiting with small groups of citizens and friends.

Monday was the last day of Lafayette’s visit. He spent the first several hours at the Town Hall, greeting the many women of Fredericksburg who lined up to meet him. Afterward, he was escorted to Mr. Gray’s Tavern for a “most sumptuous dinner” with 120 guests. A number of toasts and speeches were made in honor of the general, in memory of Washington and other heroes of the American Revolution, the City of Fredericksburg, and many others.

After dinner, Lafayette and his party entered the carriages waiting to take them to the steamboat landing in Stafford County for the next leg of his journey. “For a mile or two, the road was thronged by the eager crowd, composed of ladies of the first respectability and of all ages, who encountered on foot the danger and inconvenience of the situation, to bid him adieu again and again.”6

Not only in Fredericksburg but across the country, “...all ages and sexes and conditions, uniting and blending the testimonials of their love to one man whom all consider alike their friend…by whom the cause of liberty has been so eminently promoted throughout the world...”7

Later Life and Legacy

After his visit to the United States, Lafayette sailed back to France aboard the Brandywine, an American ship, loaded with souvenirs and presents from the grateful citizens of the United States. Among the souvenirs were several sacks of soil collected from Bunker Hill, as well as from the battlefield at Brandywine Creek, where he had been wounded in his fight for America’s freedom from British rule. This soil was heaped on his grave in Paris at his request after his death in 1834.

Lafayette’s friendship and support led to an ongoing relationship between the United States and France which has lasted to this day. Across the country, streets, towns, counties, and more are named after this brave young man who crossed an ocean to fight for our country. One of the most famous and meaningful namesakes is Lafayette Square, located across the street from the White House in Washington, D.C, a place where people still come to exercise their right to free speech, a right the Marquis de Lafayette fought for his entire life. Lafayette’s support for America and his continued battle for liberty in his native land establishes his heroism and gives Americans a reason to remember this remarkable aristocratic soldier whose efforts helped establish our United States.

To learn more about this revolutionary hero, check these resources:

Endnotes

1James Monroe to the Marquis de Lafayette, February 7, 1824., opens a new window

2Gaines, James R. For Liberty and Glory: Washington, Lafayette, and Their Revolutions., opens a new window New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2007. p. 37.

3Letter from Lafayette to John Adams, February 22, 1786, opens a new window.

4Gaines, pg. 279.

5Virginia Herald., opens a new window November 27, 1824. Pp. 2-3.

6Ibid.

7Ibid.