What is the Yugo? The Ultimate Automotive Failure

The Yugo was a small car made in the former nation of Yugoslavia that survives in the American consciousness as the ultimate automotive failure. Poorly engineered, ugly, and cheap, it survived much longer as a punch line for comedians than it did as a vehicle on the roads.

The Rise and Fall of the Worst Car in History

The story of how this particular car became the most hated vehicle in the U.S. is a comedy of errors detailed in Jason Vuic’s book, The Yugo: The Rise and Fall of the Worst Car in History. A bewildering array of capitalist hucksters and impoverished communists desperate for revenue collaborated to create the Yugo, and what could have been a great international relations victory of the Cold War was ruined the moment consumers and auto critics actually got to drive it. Vuic examines the many failures of the Yugo venture and the people involved with a keen journalistic eye and a razor-sharp wit, making this a great read for anyone interested in automotive history or 1980s nostalgia.

The story of how this particular car became the most hated vehicle in the U.S. is a comedy of errors detailed in Jason Vuic’s book, The Yugo: The Rise and Fall of the Worst Car in History. A bewildering array of capitalist hucksters and impoverished communists desperate for revenue collaborated to create the Yugo, and what could have been a great international relations victory of the Cold War was ruined the moment consumers and auto critics actually got to drive it. Vuic examines the many failures of the Yugo venture and the people involved with a keen journalistic eye and a razor-sharp wit, making this a great read for anyone interested in automotive history or 1980s nostalgia.

Malcolm Bricklin: The Man Who Brought the Yugo to America

Every story needs a compelling central figure, and that of Vuic’s book is Malcolm Bricklin, the entrepreneur who based his career on importing small cars into the US market. Vuic portrays him as a crafty manipulator and larger-than-life personality, a man steeped in the excesses of the 1980s whose grandiose marketing schemes are matched only by his love of conspicuous consumption. His entire career up to the Yugo venture is portrayed in meticulous detail, from his early days as co-founder of Subaru of America(!) in a scheme to import the Subaru 360 minicar, to his effort to con the government of New Brunswick to support his Bricklin SV-1 “safety” sports car.

An Affordable Compact Car

Although his efforts in the auto business involved a diverse array of companies and locations, they all center on a single theme—attempts to introduce an affordable, compact car into the US market, which at the time was dominated by large V-8 powered sedans. Although it’s tempting to think that Bricklin’s goal of economic success through smaller cars could have established a larger compact car market in the US, Vuic’s history of Bricklin’s many business deals makes it clear that he was far more interested in glitzy marketing deals and his massive ranch house.

Zastava Motors and Culture Clashes

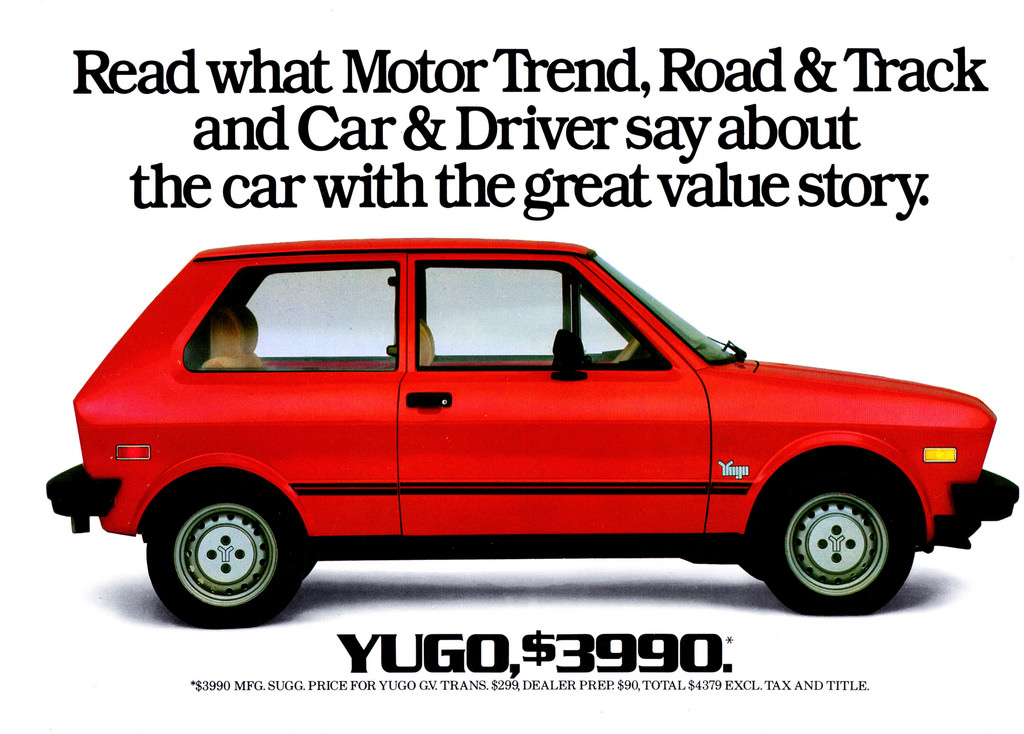

In contrast to Vuic’s wild schemes and manipulations, the Yugoslavians are portrayed as stodgy, unimaginative, and unable to succeed without the protection of their closed market. Although a communist country, Yugoslavia was not aligned with the Soviet Union, received substantial financial support from the U.S, during the Cold War, and even had the backing of noted diplomat Laurence Eagleburger in bringing the Yugo to the US. Built by state-owned Zastava Motors, the Yugo was a generic version of the decade-old Fiat 127. The age of its design and low Yugoslavian manufacturing costs meant the car could be sold for $3990 in the US market and still make a substantial profit. Vuic details how this opportunity was squandered by Zastava’s complete inability to understand the techniques for competing and succeeding in an open capitalist society. Even senior Zastava officials are befuddled by such foreign concepts as dealers being paid commission for selling cars and expensive advertising campaigns, resulting in culture clashes, and suspicion--even between Zastava’s Yugoslavian workers and Bricklin and his Yugo America employees.

What Happened to the Yugo?

The Demise of Yugo America

The book maintains a light, comedic tone up until the final chapter, which details the fate of Zastava after the demise of Yugo America and during the Yugoslavian Civil War. Thousands are laid off, Yugoslavia splinters into multiple countries, ethnic cleansing occurs under Slobodan Milosevic, and the Zastava factory is bombed, leaving shredded Yugo remains everywhere. The concept of the Yugo as a source of revenue and a symbol of national pride is utterly destroyed as Vuic details how impoverished and desperate the factory workers in Serbia, the location of Zastava’s factory, become under Milosevic.

“Yugo-nostalgia” and the End of the Yugo

Even after Milosevic was removed, Zastava never recovered, and the plant was sold to Fiat to give the nation of Serbia money in 2008. The Serbians are left with only “Yugo-nostalgia” for their past as part of a unified Yugoslavia, and the book ends with the mournful lyrics of a popular Serbian song about the days when everyone had a Yugo. This somber ending makes the reader wish that Yugoslavia could have transitioned into the modern world as a unified nation, with Zastava as a symbol of national pride. After all, if Americans gave Subaru and Hyundai a second chance after their early “econoboxes,” perhaps Zastava could have earned its redemption as well.

The Worst Cars Ever Made

Want to read about other not-so-great (okay, maybe terrible?) cars of all time? These resources will give you even more to explore.