By Kara Rockwell

Stafford County has a rich Civil War history including a naval battle, cavalry skirmishes, and Union encampments. Many of these Civil War sites can still be visited today.

Aquia Landing and the Potomac Creek Bridge

Today. Aquia Landing is a recreational park for fishing and swimming, but during the Civil War, it was an important transportation link. Aquia Landing is on Aquia Creek where it empties into the Potomac River. It was the northern terminus of the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad (RF&P) as well as a port on the Potomac River. Steamships to Washington and the railroad to Richmond allowed for easy access between the North and the South. Recognizing this, when Virginia seceded, troops from the state took control of Aquia Landing and established fortifications

to protect it. At about the same time, the Union army seized the steamships traveling along the Potomac and made them into gunboats.

From May 29 to June 1, 1861, there were a series of skirmishes at Aquia Landing between Union gunboats and the Confederate defenses. By the end of the day on June 1, 1861, the Union commander, James Harmon Ward, disengaged. By that time, most of the Confederates had been pushed back from their positions. On the Confederate side, there were no deaths and no injuries, but there was a great deal of damage to the wharf, its buildings, and the railroad tracks at Aquia Landing. On the Union side, there were no deaths but one injury. There was also damage to two of the gunboats.

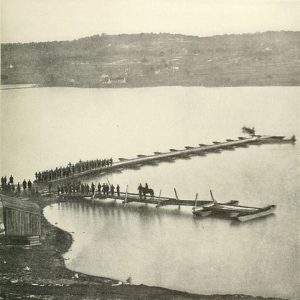

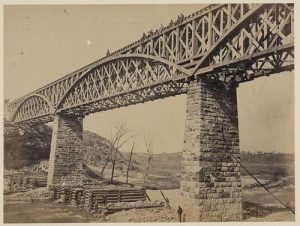

Aquia Landing changed hands in the spring of 1862. When the Union army began to take control of the entire RF&P Railroad, the Confederates burned the facilities at Aquia Landing and destroyed the railway bridges over Accakeek Creek, Potomac Creek, and the Rappahannock. In May 1862, Union army engineer, Colonel Herman Haupt was ordered to restore the RF&P railroad, including rebuilding the Potomac Creek Bridge. Within 12 days, a bridge was built. Four days after that, trains began running. President Abraham Lincoln described Haupt’s bridge as nothing “but beanpoles and cornstalks.” RF&P rail lines, as well as facilities at Aquia Landing, were destroyed and rebuilt several times over the course of the war. After the war, a new rail line was built between Fredericksburg and Quantico which opened in May 1872. The old line between Brooke and Aquia became present-day route 608 (Brooke Road.) [Sources: Conner, Albert, 76-77, 87-88; Eby, 92-95; Musselman, 7-9, 20, 31-32]

Today you can visit Aquia Landing as well as the ruins of the old Potomac Creek Bridge. Aquia Landing is located at the end of Brooke Road and is open year-round. In addition to being a Virginia Civil War Trails site, the park is also an Underground Railroad Network to Freedom site. Many escaped slaves passed through Aquia Landing on their way to freedom.

The ruins of the Potomac Creek Bridge are located off of Leeland Road.

Falmouth Beach

Falmouth Beach is the site of "The Crossing," where a slave named John Washington arrived after crossing the Rappahannock River to freedom. Across the river is Old Mill Park in Fredericksburg where Washington began his journey. Both sites are on the Trail to Freedom, opens a new window.

By April 18, 1862, Union troops had arrived at Falmouth, across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg. John Washington had been working at the Shakespeare Hotel when word arrived of the Union army camping in Falmouth. Many of the white citizens left town or hid. After speaking to his owner and returning the hotel keys to the proprietor’s wife, Washington walked through Fredericksburg. He and two other men left town and headed toward the river and Falmouth. Some Union soldiers called out and asked if anyone wanted to cross. Washington said he did and he crossed the river to freedom.

Falmouth Waterfront Park is located off of River Road in Falmouth and is open March through Labor Day.

(Sources: Washington, 45-47; Hennessey “Exodus”)

Hartwood Presbyterian Church

In February 1863, Confederate General Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry led raids in the area of Hartwood Church. The plan was for General “Fitz” Lee to lead troops from the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Virginia Cavalry regiments to go behind Union lines. On February 24, 1863, Lee and his troops left Culpeper and crossed the Rappahannock River at Kelly’s Ford. On February 25, they reached the picket lines near Hartwood Presbyterian Church, where they were able to overtake the troops, and then pressed on toward Falmouth. In the area near Berea Church, Union defenses were able to overtake the Confederate Cavalry, which then retreated across the Rappahannock River to Fauquier County. (Sources: Conner, Albert, 88; Musselman, 49-50)

Hartwood Presbyterian Church and Berea Church are still active churches. Information about locations and services can be found on their Web sites.

Stafford Civil War Park

During the winter of 1862-1863, the Union army had winter quarters here in Stafford County. Although there were camps throughout the county, the remains of one winter camp can be seen at the newly opened Stafford Civil War Park. Here, members of the Union Army’s 11th corps were encamped, arriving around February-March 1863, and remaining until the spring. They constructed huts out of wood and canvas and built batteries to protect the camp and the creek from possible Confederate attacks. (Sources: Kamphoefner, 138-141)

The park is located off of Mount Hope Church Road in Stafford County. At the park’s five stops, you can see the ruins of one of the Union Army’s winter camps as well as the remains of three Union batteries, as well as those of a corduroy road and an old sandstone quarry, along with the ruins of a bridge dating to about 1837. Admission is free, and the park is open 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., Mid-March to October 31 and 8 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., November 1 to mid-March.

White Oak Civil War Museum

Anyone interested in the Civil War history of Stafford County should visit the White Oak Civil War Museum. Located in the old White Oak School, it was honored as the Civil War Trust Discovery Trail Site of the Year in 2011. The museum interprets the Civil War in Stafford County and its effects on the citizens and the land. The exhibits include artifacts found in various Union encampments throughout the county, replicas of winter camp huts, and much more.

The museum is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. every Wednesday through Sunday. It is located at 985 White Oak Road.

Stafford County was greatly affected by the Civil War. At the end of the conflict, Stafford suffered both financial and population losses. (Musselman, 78-79). In addition, woodlands were lost as the trees were cut down for firewood and huts. It took many years before the woodlands recovered. (Musselman, 84)

Other significant Civil War sites include Chatham Manor and Ferry Farm. Chatham Manor, now the headquarters for the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, was the Union headquarters in Stafford County. Hours are 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily. Ferry Farm, George Washington’s boyhood home, was a staging area for the Union army during the Battle of Fredericksburg. It is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. daily from March through December.

These places provide a clearer view of what happened in the county. Learn more about Stafford’s Civil War sites and county history by reviewing these resources.

Bibliography:

Print Resources:

Germans in the Civil War: The Letters They Wrote Home, edited by Walter D. Kamphoefner and Wolfgang Helbich, translated by Susan Carter Vogel.

A History of Our Own: Stafford County, Virginia, by Albert Z Conner, Jr.

John Washington’s Civil War: A Slave Narrative, by John Washington. Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Crandall Shifflett

Lincoln in Stafford, by Jane Hollenbeck Conner

The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union, by Bell Irvin Wiley

Sinners, Saints, and Soldiers in Civil War Stafford, by Jane Hollenbeck Conner

A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom: Including Their Own Narratives of Emancipation, by David W. Blight

Stafford County in the Civil War, by Homer D. Musselman

They Called Stafford Home: The Development of Stafford County, Virginia, From 1600 Until 1865, by Jerrilyn Eby

The Union Cavalry Comes of Age: Hartwood Church to Brandy Station, 1863, by Eric J. Wittenberg

Virginia Shade: An African American History of Falmouth, Virginia, by Norman Schools

Online Resources:

The Free Lance-Star: “White Oak Museum Tells Stafford’s Story,” by Jonas Beals. 11/24/2009. https://fredericksburg.com/local/white-oak-museum-tells-stafford-s-story/article_85e88b89-ecd8-55cb-9f31-ca1a6fa9f1df.html

Mysteries and Conundrums: “The Evolution of Aquia Landing,” by John Hennessey. http://npsfrsp.wordpress.com/2010/08/09/the-evolution-of-aquia-landing/

Mysteries and Conundrums: “The Exodus Begins: John Washington’s Greatest Journey” by John Hennessey. http://npsfrsp.wordpress.com/2012/05/02/the-exodus-begins-john-washingtons-greatest-journey/