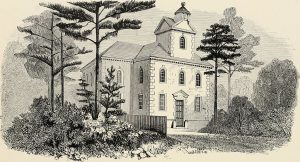

Travelers who take a turn off of busy Route 1 near Aquia Harbor find themselves viewing a living monument to colonial Virginia's past. Protected from the surrounding sprawl by its location, nestled on a hilltop surrounded by trees, this beautiful church dates to the decades before the Revolutionary War. Its long and sometimes difficult history—preserved in bricks, stone, and written memories, includes tales of preachers, firebrands, soldiers, and star-crossed lovers.

Visitors may view the outside and the grounds of Aquia Episcopal Church at any time during daylight hours. However, those who wish to see the church's interior need to contact the church office to arrange a tour.

On the day of my visit, Dennise LaBarre, the Parish Secretary, kindly guided me through the doors of the lovely, old church. Its interior is striking for what isn't there: no stained glass, no ornate carving. Light streams through the tall windows, adding a grace note to the rather plain yet handsome pews and a remarkable three-tiered pulpit.

Although the church is not exactly as it was in the colonial period, very little has changed. In a way, the hard times that Stafford County suffered both before and after the Civil War worked to preserve the church in its older style. This simple elegance reflected the style of preaching of the 1750s which mistrusted more opulent ways.

As to the exterior, Aquia Church was built in the shape of a Greek Cross, using brick laid in the Flemish bond pattern. The famed Aquia Creek sandstone (also called "Freestone") was used in the doorways, window keystones, quoins (cornerstones) and possibly in the original flooring. The Freestone has also been used in other significant buildings, including the Federal Capitol, the White House, Mount Vernon, Gunston Hall, and the Town Hall in Fredericksburg.

The Parish's Beginnings

In the days before the separation of church and state, Aquia was part of Overwharton Parish, which also included Old Potomac Church, once very large and long since deserted. This parish served the northern portion of Stafford County. The southern portion was served by St. Paul's Parish. The parish's first rector was Reverend Morgan Godwyn (1667 - 1670).

Overwharton Parish was named for the home of its second minister, "Parson" John Waugh. This fiery individual frequently performed marriages for runaway couples in Stafford's early days. He served as rector from 1670 to 1700, at last retiring to his plantation when his license was revoked. "Parson" Waugh was also known for his "tumult" of 1688-89 when he preached of a supposed plot against the Protestants by Catholic members of his community. His fomentations caught the attention of the populace, and soon the colonial government:

-

1689 (VIRGINIA) Parson [John] WAUGH'S Tumult

..."But in Stafford, there was another story. There the people abandoned their plantations and arrayed themselves in arms...The Maryland authorities apparently interpreted this activity as preparations for an invasion of their territory...The BRENTS who lived in Stafford for many years were Catholics. They had been discreet in their relations with their Protestant neighbors and had never been Molested...But Burr HARRISON'S news from Maryland offered an opportunity for fanatical agitation and the incumbent of Overwharton Parish took full advantage of it. This Parson John WAUGH had already been in trouble with the authorities for his lack of respect for the law. He was apparently a natural agitator, what was called at the time "of enthusiastic principles" and courted popularity. Egged on by his son-in-law, the second George MASON, WAUGH'S sermons now stirred the community to a frenzy...Over these troubled waters, Parson WAUGH rode the whirlwind. Beginning as a colonial Titus Oates, under the inspiration of his fellow enthusiast, John COODE, the whilom parson of Maryland who was about to lead a successful revolution in that province, WAUGH gradually developed into what appeared for a moment to be a menace to the Virginia government. From general thunder against the Catholics, he evolved the more dangerous thesis that there "being no King in England, there was no Government here," and that the people should remain in arms in their own defense. This advice, smacking significantly of the doctrine which Lord Baltimore charged FENDALL with preaching in Stafford in 1681, was followed, the alarm spread to the Rappahannock settlements, and serious consequences were averted only by renewed vigorous action on the part of Messrs. SPENCER, ALLERTON, and LEE. Assuming the authority of the entire council for the emergency, they…arrested the ring leaders, WAUGH, HARRISON, and WEST, forbade the parson to preach, and suspended George MASON from the command of the Stafford militia...Parson WAUGH was eventually brought before the General Court at Jamestown and there "made a publick & humble acknowledgement...with a hearty penitence for his former faults and a promised obedience for the future..."

Virginia Historical Magazine, volume 30, pp. 31-37

The Scottish Rectors

From 1711 to 1738, Reverend Alexander Scott served as rector. He lived at an estate called "Dipple," on Chopawamsic Creek, named for his home in Scotland. "Dipple" and its acres became part of Quantico Marine Corps Base during World War II. At that time, its local graves, including Alexander Scott's, were moved to Aquia Cemetery. Alexander Scott left his parish their silver communion set: "A silver pottle flagon, a silver pattin and good substantial silver pint chalice and cover." Childless himself, he also gave a significant sum to help benefit three needy children with clothing and schooling.

He was followed by his fellow clergyman, John Moncure. Also hailing from Scotland, Reverend Moncure was not at all a rich man in worldly possessions, and his courtship of wealthy Dr. Brown's daughter was met with some consternation. His new father-in-law, while not forbidding the marriage, refused to pay her dowry until such time as he was convinced that the couple would remain happily united. Despite his skepticism, the two fared well enough "on love without other sauce." The complete story, as related in a letter from the couple's daughter, may be read online here.

It was under John Moncure's leadership that the church we see today was built. In 1751, the Vestry of Overwharton parish announced their intention to build this church in the Virginia Gazette, while advertising for a builder. Mourning Richards, master builder hailing from King and Queen County, was chosen as the contractor. William Copein served as the stone mason. Copein would later work on Pohick Church in Fairfax County.

A Fire in the Night

The building was almost completed in 1755 when a fire destroyed the interior, leaving only the outside walls intact. The blaze caused by careless workmen who left a fire "too near the Shavings, at Night, when they left off work."

Richards had been paid 110,900 pounds of tobacco, a considerable sum. The fire which destroyed most all the completed work left him in a very difficult financial position. To finish the church, Mourning Richards was granted money from the House of Burgesses, through levies upon the colony's citizens. These levies were protested by Virginians who were already showing signs of chafing at British laws.

The church was completed in 1757. Among its notable features are four black, wooden tablets behind the altar. Upon these, lettered in white by William Copein, are the Ten Commandments, the Apostle's Creed and the Lord's Prayer. In a few years' time, Reverend John Moncure and his wife would be buried in a vault under the Chancell.

The Church Loses Prominence

After the American Revolution, the Church of England was no longer funded by public money. Furthermore, this was the time of the Great Awakening. New denominations such as Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, and other Separatists drew possible parishioners away from the Episcopal churches. Aquia and Old Potomac suffered drastic membership losses due to this as well as the push for some families to move farther west. According to 19th-century accounts, the exhausted soil was also a factor. Unable to afford its own rector, Aquia shared its minister with other churches up until the middle of the twentieth century.

Aquia Church was much disheveled when William Meade first came to it in 1838 to serve as assistant bishop. Broken windows, as well as overgrown pathways, marred its appearance. Still and all, it was far better off than Old Potomac Church. Potomac had long since been abandoned as a house of worship. Meade reported that at one time the venerable walls had housed caterpillars, part of a failed attempt to manufacture silk in the Old Dominion.

When Meade returned almost 30 years later, Aquia Church was greatly altered. Freshly painted and repaired, the church housed a sizeable congregation, many of whom were descended from John Moncure. Bishop Meade predicted an encouraging future for "Old Aquia Church," but the war clouds gathering on the horizon would stymie any significant recovery for decades to come.

The Civil War Comes to Stafford

Nearby Aquia Landing was a strategic depot for Federal troops during the War. Through those years, approximately 100,000 troops in blue encamped in Stafford. Like many strong and large buildings, Aquia Church was taken by the military. It is true that members of the 17th Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment used the church for services in February of 1863. However, the old pews were used for stabling horses. As they will, the bored animals gnawed or "cribbed" the top of the railings, necessitating that the pews be trimmed down to a lower height after the War. Names and units of the occupiers can be seen cut into the sandstone and in the tower.

The Aquia Church grounds were used as a hospital and for an encampment by the Yankees. As might be expected, some of these Federal soldiers were buried amongst the parishioners. David W. Judd, the correspondent for New York Times, wrote that the locals, though studiously friendly by day were equally dangerous by night and mentions without remorse the desecration of a tombstone and a grave.*

After the War

The thousands of troops bivouacked in Stafford scavenged for what they needed and left few trees standing. Naturally, erosion followed, stripping the soil of its usefulness. Many left the country, and those who remained had to cope with the wretchedness of economic ruin. Roads were often impassable. As a result, several Episcopal chapels sprang up throughout the countryside, including Rockhill Chapel, Clifton Chapel, and the Church of the Holy Spirit. Many of these would eventually change hands or fall into disuse because of the rise of the automobile.

Aquia Church herself was hit hard by the War. Upon assuming the Rectorship, Reverend J. M. Meredith found himself with eight communicants and a church in serious need of repair. He spent his own money for this and collected very little of his promised salary. Eventually, he would move on to Bruton Parish in Williamsburg, Virgina.

The Twentieth Century: A Time of Renewal

After the Civil War, more extensive repairs were undertaken by a member of the Moncure family, in exchange for permission to bury additional members of the family in the vault under the Chancel. However, with no money forthcoming for luxurious additions such as stained glass, Aquia retained much of its original character with an exception or two. For example, in the 1930s, the wooden Chancel floor was replaced with marble.

In 1954, new heating and lighting were installed. Aquia Church became self-supporting in 1956, with 165 members. This financial independence from the diocese was a historic first for the parish. In 1960, the ground was broken for the Parish House which would provide increased chances for fellowship for the church's increasing membership.

Indeed, as the decades progressed, it became clear that Stafford's growth surge was continuing, and there clearly was a need to protect the church from the encroaching development. In 1974, Anne E. Moncure conveyed lands to the church to protect its natural setting and increase the size of its graveyard for future internments.

In 2001, Aquia Church marked its 250th anniversary with a five-month-long celebration, including services performed much in the same manner as they would have been in 1751. In an article written for the Free Lance-Star, the Reverend Cuthbert Mandell, Aquia's rector, noted that the church's mission, to baptize others and teach them about Christ's ways, has remained constant for 250 years.

Aquia Cemetery

Behind the church is Aquia Cemetery. Some of its tombstones date back centuries; others date to just the past few years. All of them mark citizens -who made Stafford their resting place. Each has his or her own story.

As just one example, the remains of Kate Waller Barrett, wife of Rector Robert S. Barrett, lie in this ground. Born in 1857 and having survived a childhood set in the Civil War, this Stafford native married the young minister and joined him when his work took him to the slums of Richmond. After his early death from typhoid, Kate, who held a medical degree, pursued her good works and went on to be a principal founder of the Florence Crittendon Homes for Unwed Mothers. She also organized the National Council of Women and fought for the rights of abused women.

Rectors and Historical Notes for Aquia Church:

- 1667-1670: Reverend Morgan Godwyn serves as the first Rector of Overwharton Parish (Potomac). His brief years here were marred by court battles with his Vestry.

- 1670-1700: "Parson" John Waugh served as Rector during a heavy growth period. He was known to often marry runaway couples against their parents' wishes, without license or banns being read. Finally, his license was revoked, and he retired to his plantation, Overwharton. He was also responsible for "Waugh's Tumult." In the intervening years, it is known that Reverend John Fraser served as Rector.

- 1711-1738: Reverend Alexander Scott served as Rector, living at an estate called "Dipple" on Chopawamsic Creek (now part of Quantico Marine Corps Base). Alexander Scott left the Parish its Communion Set and gave a significant sum to help benefit three needy children with clothing and schooling.

- 1738-1764: Reverend John Moncure served as Rector until his death. In later years, he lived at Clermont in Stafford County. He was much beloved and is buried, along with his wife and some of his descendants, in the Chancel under the Church.

- 1751: Plans are drawn for the current Aquia Church

- 1755: Fire destroys much of the new building

- 1757: Aquia Church is at last completed

- 1764-1773: Reverend Clement Brooke, a loyalist, and a member of the Committee of Safety in Stafford serves as Rector.

- 1785(?)-1804: Reverend Robert Buchan serves as Rector. His home, "Cherry Hill," is located north of Potomac Creek.

- 1804-1819: Position of Rector was vacant

- 1819-1822: Reverend Thomas Allen served as Rector. According to Bishop Meade's writings, he worked diligently to revive the church. Reverend Allen preached at both Dumfries and Aquia as there was not money enough to pay the salary of two rectors

- 1822-?: Reverend Prestman became Rector and continued to work to revitalize the Church

- ?-1852: Reverend Johnson served as Rector

- 1852-1854: Reverend John Towles served as Rector. During this period, the church was beginning to undergo repairs, and the Vestry was reorganized.

- 1855-1859: Reverend Henry Wall served as Rector, preaching alternately at Aquia and at Lamb's Creek Church in King George County.

- 1859: Reverend G. L. Machenheimer is offered a half-time position as Rector.

- 1862-November, 1864: Rectorship vacant

- November of 1864: Reverend J. M. Meredith, formerly chaplain of the 47th Va. Infantry became Rector. Rev. Meredith used his own funds to "repair the injuries done the Church by the Yankees during the War." He continued to serve, at least until 1868, with little recompense, finally leaving to become Rector of Bruton Parish in Williamsburg.

- 1876: Robert S. Barrett, Husband of Kate Waller Barrett, serves as Rector

- 1877: 1880 Reverend Meredith returned to Aquia. After his retirement, he continues to preach at nearby Rockhill Chapel. He lived at "the Rectory."

- The following gentlemen served as Rector in the proceeding years:

- 1884-1886: Reverend G. M. Funston

- 1886-1888: Reverend T.C. Page

- 1889-1895: Reverend J.H. Birckhead

- 1897-1901: Reverend J. Howard Gibbons

- 1901-1910: Reverend E. B. Burwell

- 1911-1912: Reverend C.P. Holbrook

- 1911-1916: Reverend George Victor Bell

- 1917-1921: Reverend Joseph Baker

- 1921-1924: Reverend John Fleming Wren Field, co-Rector of Trinity Church, Fredericksburg, Virginia

- 1925-1929: Reverend Charles Wilford Sheerin, co-Rector of Trinity Church, Fredericksburg, Virginia

- 1929-1948: Reverend Henry Heaton serves as Deacon in charge. For the first time in many years, Aquia Church had a pastor of its own. In 1938, Reverend Heaton was ordained and served as Rector.

- 1930s-1940s: Church renovations take place. Graveyard extended to include the graves moved by the U.S. Government because of the taking of land for the U.S. Marine Corps. These included the following cemeteries: Dipple, Stony Hill, and Somerset.

- 1949-1951: Reverend John E. Williams

- 1952-1954: Reverend Wilbur M. Sims

- 1954-1959: Reverend Palmer Campbell

- 1960-1965: Reverend Arthur Boothe

- 1966-1969: Reverend Ronald Pedigo

- 1970-1984: Reverend William D. Boyd

- 1986-1996: Reverend Joseph Reid Kerr, III

- 1999-2000: Reverend Ronald Livingston Robinson

- 2001-2010: Reverend Cuthbert H. Mandell

- 2013 – Present: Reverend John "Jay" G. Morris, III

Bibliography

Print Resources:

- "Aquia Church: Architectural Gem," by James C. Wilfong, Fredericksburg Times, February, 1980, pp. 14-16.

- Colonial Churches in Virginia by Henry Irving Brock.

- Old Churches, Ministers, and Families of Virginia by William Meade.

- *The Story of Aquia Church by Thomas M. Moncure, Jr. & Molly A. Pynn.

- Virginia's Colonial Churches: An Architectural Guide; Together with Their Surviving Books, Silver & Furnishings by James Scott Rawlings.

Online Resources:

- "Aquia Church: A Survivor," May 31, 2010, via The Free Lance-Star

- "Aquia Episcopal Returns to 1751 for Celebration," June 4, 2001, via The Free Lance-Star

- "In Praise of Country Churches," New York Times, September 26, 1999

- Overwharton Parish Register: 1720-1760