To fight a duel, whether with swords or pistols, remains one of the most romantic and violent tropes of the 17th through the 19th centuries. From Alexandre Dumas’ D'artagnan to the Firefly episode, “Shindig,” the deadly side of an old and polite society remains fascinating to today’s audiences. But are the scenarios laid out in fiction exaggerated for our amusement? Surely, no civilized people would resort to such violence over mere words—or, would they?

To fight a duel, whether with swords or pistols, remains one of the most romantic and violent tropes of the 17th through the 19th centuries. From Alexandre Dumas’ D'artagnan to the Firefly episode, “Shindig,” the deadly side of an old and polite society remains fascinating to today’s audiences. But are the scenarios laid out in fiction exaggerated for our amusement? Surely, no civilized people would resort to such violence over mere words—or, would they?

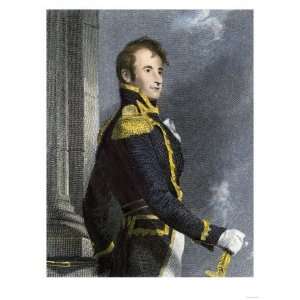

Andrew Jackson, later the seventh President of the United States, fought in more than a dozen duels and received a bullet in his lung from one of them that remained there until his death nineteen years later. What did he duel over? His first opponent was an attorney who made him look foolish in court. It ended with shots fired in the air. He later chose to duel the first governor of Tennessee, a political rival, when that man accused him of adultery—technically true as Jackson’s wife’s divorce from her first husband wasn’t finalized when she remarried. And what was the cause of the duel that got him a bullet in the lung? An argument about a horse race. Wounded for life or not, Andrew Jackson won that duel. He took the hit in the chest and then killed his opponent.

No, the tales told about dueling were not very much exaggerated. The Duelling Oaks in New Orleans were once the site of daily combat. However, not all duels were lethal. Though related to the medieval concept of Trial by Combat, where deadly force would allow God to decide the virtue of a case, many combatants were content to draw first blood with their blades or just shoot their pistols into the air. Sometimes, it was more a question of being willing to fight.

Pistols v. Swords

Pistols were around in the 17th century, but they were heavy and awkward. Not a very gentlemanly choice. Dueling was about honor which is what gentlemen (a technical and legal as well as a social term) were expected to protect. It was certainly possible for those of lower social station to duel, but it was understood that duels must be between equals. A gentleman would not be expected to accept a duel offered to him by a tradesman or a servant. It was, to use a popular phrase, beneath his contempt. So, when elegance and propriety were the order of the day, a gentleman in the 17th and throughout most of the 18th century would probably have used his sword, frequently carried at his side.

With improvements in gun manufacture came the advent of sleek dueling pistols. These instruments of death were made of the finest materials, often in England. The set at right belonged to the famous Virginia politician John Randolph of Roanoke. The image is provided courtesy of the Virginia Museum of History & Culture, and the item itself is on display as part of their Story of Virginia showcase. Randolph was known for having a fiery temper, and his insult to Secretary of State Henry Clay on the Senate floor in 1826 resulted in a duel. On another occasion, Randolph horse-whipped a fellow politician who he felt had insulted him. He was not the only legislator to do so.

The Code Duello

Proper duels of recent centuries were very formal affairs with strict rules designed to keep things relatively civilized, e.g. prevent feuds lasting for generations, exhausting some peaceful alternatives beforehand, and making sure medical assistance was available. The Code Duello was developed in Ireland in 1777 and was followed more or less in Europe and America. In 1838, John Lyde Wilson, once governor of South Carolina, did much to codify dueling rules in a more American way in a small but extensive book entitled, The Code of Honor.

Two Famous Duels

Burr v. Hamilton

On July 11, 1804, U.S. Vice President Aaron Burr shot and killed former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (he of the ten-dollar bill) in a duel. The ensuing scandal marred Burr’s reputation irretrievably, preventing him from rising further politically.

On July 11, 1804, U.S. Vice President Aaron Burr shot and killed former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (he of the ten-dollar bill) in a duel. The ensuing scandal marred Burr’s reputation irretrievably, preventing him from rising further politically.

The details of the long-standing, bitter relationship are both personal and political. In 1804, Burr—who, having been dropped from Jefferson’s ticket as Vice President, was running for the governorship of New York—took extreme offense at the public insults of a political nature made by Hamilton not only in that campaign but in the years leading up to it. Indeed, Hamilton’s father-in-law lost his Senate seat to Burr in 1791. Dueling, while not common in the North, was very much an accepted part of their society. Both men had participated in duels before. What was unusual this time is that Burr killed Hamilton (most duels did not end in death) and was brought up on murder charges in New York and New Jersey, though nothing came of them. While the dust settled Burr fled to his daughter’s home in South Carolina and then returned to Washington, D.C. to finish out his initial term as Vice President.

A Naval Hero

On March 22, 1820, Stephen Decatur fought James Barron at the infamous dueling grounds in Bladensburg, Maryland. Decatur had become the youngest naval captain in U.S. history and was a hero of the first and second Barbary wars who rose to the rank of Commodore. James Barron, another naval officer, blamed Decatur for his five-year suspension without pay for being unready for battle, as Decatur was part of the court martial board and took command of Barron’s ship. Decatur, unaware that when Barron’s suspension was up, he was trying unsuccessfully to get reinstated into the Navy, called him a coward for avoiding service in the War of 1812. Even so, this tragic duel between two heroic men could have been avoided were it not for the intervention of their “friends.” Seconds are supposed to look after the interests of their friends, the combatants, and preferably lead them to a gentlemanly agreement without resorting to violence. But both Barron’s and Decatur’s seconds had knavish reasons for wanting Stephen Decatur dead, and that indeed is what happened.

Local Tragedies

Residents of Fredericksburg, Stafford and Spotsylvania were certainly not immune to the possibility of an argument resulting in a duel. Two fatal encounters occurred at what is now one of Fredericksburg’s most-enjoyed recreation areas:

The Ritchie-Glassell Duel

“The narrow pathway between the Alum Spring rock and the mill pond was the Dueling Path. Robert A. Hodge, the person responsible for the present Alum Spring Park's existence, tells its tragic story in this excerpt from his book, Alum Spring Park: A History:

“In or about March of 1790 the members of the Masonic Lodge No. 4 of Fredericksburg gave a large and brilliant ball. Among those in attendance were members William Glassell and Robert Ritchie.

“William Glassell, a native of Scotland, was a successful merchant and respected citizen who had married a sister of Anthony Buck, the latter a highly esteemed auctioneer of the town. Glassell had escorted to the ball a young, attractive and respected orphan girl who was living in his home.

“Mr. Ritchie was originally from Essex County down the river from Fredericksburg, but doing business in the town. He was not married. During the course of the evening at the Masonic Ball, and somewhat under the influence of wine, Ritchie offered a distinct insult to Glassell's young guest, then refused to make a suitable apology when called upon to do so.

“Glassell sent a formal challenge which Ritchie accepted, choosing pistols as the weapons and Alum Spring as the place. Ritchie, knowing Glassell was an excellent marksman, was concerned enough over the event to make his will which was dated 27 March 1790 and if probated left all his legacy to his sister, Elenora.

“Glassell had second thoughts and, through friends, attempted to get Ritchie to reconsider. Ritchie refused and the duel took place on the pathway along the Alum Spring Rock in front of the clear mill pond.

“At first shot, Ritchie fell to the ground, mortally wounded. Glassell hurried to his side and asked forgiveness, which was refused. After Ritchie's death, a murder warrant was issued. Glassell was taken before a magistrate, but was acquitted.

The Thornton-Conway Duel

“Cousins William Thornton and Francis Fitzhugh Conway were each attracted to a young niece of James Madison. Miss Nellie Madison was a Christmas guest at Chatham in this year of 1803.

“Cousins William Thornton and Francis Fitzhugh Conway were each attracted to a young niece of James Madison. Miss Nellie Madison was a Christmas guest at Chatham in this year of 1803.

“William and Francis arrived at the Chatham festivities on horseback and their horses were stabled. Francis had adorned his horse with a brand new handsome bridle and during the evening made veiled references to Miss Nellie as to the ‘surprise’ he would reveal later that evening.

“Unfortunately, when departure time came and Francis was primed to ‘show off,’ the groom had switched bridles on the horses and it was William's horse which made the greater impression on Miss Nellie.

“Angrily, Francis accused William of having bribed the groom. The denial simply aggravated the argument and the end result was a challenge to a pistol duel to take place at the Alum Spring site.

“They met on the narrow pathway between the Alum Spring rock and the mill pond. At the word ‘fire’ both shots sounded almost simultaneously and each bullet passed through the region of the bladder in each combatant.

“Thornton was able to ride back to Fredericksburg where his stepfather, Dr. Robert Wellford, apprehended that the wound would be fatal and William's death occurred the same hour that Francis died.

“The Virginia Herald of February 17, 1804, carried a notice that a brace of brass-barreled pistols was found near the Alum Spring and could be claimed from William or John Rutter.”

From “Alum Spring Park: A Walk Through History,” by Barbara Crookshanks

Leaving town didn’t mean leaving behind the dangerous dueling customs. The local newspapers dutifully reported when former members of the community met their ends in other, usually Southern states:

Virginia Herald, Nov. 9, 1808.

Another Fatal Duel -- An affair of honor was, on Saturday last, determined in Maryland, between Peter V. Daniel, esq. and Capt. John Seddon, both of Stafford, in this state. The latter received his antagonist’s ball in his right side, languished till about 8 o’clock on Monday morning, and died.

Virginia Herald, Saturday, Nov. 5, 1808.

Fatal Duel -- Doctor Benjamin Powell, late of this county, was killed in a duel, near Charleston, South Carolina, on the 23d ult. by a Mr. McMillan of that city.

Fredericksburg News, May 24, 1850

“A Duel”

Mr. A. Walker, formerly of this place, exchanged a shot on the 13th inst., with Dr. Kennedy. Walker was editor of the Delta, and Kennedy of the true Delta, and both of New Orleans -- They fought at Bay St. Louis, Miss., without damage to either, and parted after a single fire.

The fight arose from some scathing commentaries in the true Delta, upon the late correspondence of Mr. Walker, with Thos. H. Benton for which he certainly deserved a severe rebuke.

A writer in the Mobile Tribune says: this is but the “beginning of the end. We may look out for duel No. 2.” So we presume there will be another fight.

Dueling Dissolves

Cultural touchstone or not, dueling led to too much tragedy to be ignored by the authorities forever, and the death of Alexander Hamilton was certainly fodder for the anti-dueling movement. On January 6, 1810, a law was passed in Virginia to make a death by duel merit capital punishment and also addressed “fighting words” that might lead to duels.

Even though dueling was officially outlawed in the Old Dominion, it still happened frequently with limited prosecutions or convictions. On March 1, 1888, the editors of rival Culpeper newspapers had at it over what one deemed a grievous insult. This was not a formal duel. It adhered to no code and there were certainly no seconds although one of the participants hoped to settle the matter through friends. But his opponent wanted blood:

Free Lance

TUESDAY, MARCH 6, 1888

VIRGINIA EDITORS IN A DEADLY DUEL

A Newspaper War Ends in a Tragedy--Ellis Williams Shot Through the Heart, and Edwin Barbour Seriously Wounded--A Fight (illegible)

CULPEPER, VA, March 1. -- One of the most desperate and deadly shooting affrays that ever happened in this vicinity occurred here this morning, between Edwin Barbour, editor of the Piedmont Advance, and Ellis B. Williams, son of Governor Williams, editor of the Culpeper Exponent, resulting in the death of Williams and the serious wounding of Barbour. Both are young men and their families are highly-connected. The cause of the trouble seems to have grown out of a newspaper article, in the shape of a letter, dated from Washington and Signed “Jack Clatterbuck,” which was published some weeks ago in the Piedmont Advance.

The rest of the article is available here online. The Barbour-Williams Duel was just one example in a tradition of hot-tempered newspaper editors who wielded pistols as well as pens to make their marks.

After the Civil War, gentlemen seemed to have lost their taste for unnecessary bloodshed. Perhaps a public turning point for many was in 1884 when John S. Wise, a veteran, lawyer, and son of a former Virginia governor, published a refusal to duel his would-be opponent in the newspaper. Because of his war record, he was known not to be a coward, and was also known as a man devoted to his family and state who had no need to further prove his worth.*

Dueling of the kind practiced in early America with all of its elaborate formalities became extinct long ago, but it lives on with considerably more verve and less tragedy in cinema, history, and fiction.

Additional Resources

From Our Catalog

Gentlemen's Blood: A History of Dueling from Swords at Dawn to Pistols at Dusk by Barbara Holland

The Last Duel: A True Story of Crime, Scandal, and Trial by Combat in Medieval France by Eric Jager

Methods and Practice of Elizabethan Swordplay by Craig Turner and Tony Soper (eBook)

Pistols and Pointed Pens: The Dueling Editors of Old Virginia by Virginius Dabney

Tales of the Gun: Dueling Pistols: The Etiquette Of Death (DVD)

A complete list of our related materials, To Fight a Duel, is also available.

These articles may be accessed through the CRRL’s JSTOR database:

“The Actionable Words Statute in Virginia.” S. J. B. Virginia Law Review, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Jan., 1941), pp. 405-414

Published by: Virginia Law Review

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1067963

“The Death of the Duel: The Code Duello in Readjuster Virginia, 1879-1883.” James T. Moore. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 83, No. 3 (Jul., 1975), pp. 259-276

Published by: Virginia Historical Society

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4247961

“Dueling in the District of Columbia.” Myra L. Spaulding. Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. , Vol. 29/30, [The 29th separately bound book] (1928), pp. 117-210

Published by: Historical Society of Washington, D.C.

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40067423

“Duelling in Virginia.” Robert Reid Howison. The William and Mary Quarterly, Second Series, Vol. 4, No. 4 (Oct., 1924), pp. 217-244

Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1919281

“The Smith-Holmes Duel, 1809.” Richard Xavier Evans. The William and Mary Quarterly, Second Series, Vol. 15, No. 4 (Oct., 1935), pp. 413-423

Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1919790

“Southern Chivalry and Total War.” R. M. Weaver. The Sewanee Review, Vol. 53, No. 2 (Spring, 1945), pp. 267-278

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27537582

On the Web:

Duel! From the Smithsonian magazine

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/duel.html

Tells of Washington’s, and Lincoln’s brushes with duels and Andrew Jackson’s more sanguinary experiences as well as that of the poet and master duelist, Alexander Keith McClung.