By Dan Enos

Home to sprawling plantations, the even more sprawling Fort A.P. Hill, and historic sites such as assassin John Wilkes Booth’s death place and explorer William Clark’s birthplace, Caroline County is an archetypal rural Virginia county, far closer in spirit to the somnolent Clayton County from Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind than the avant-garde art and literature communities of cities like New York and Madrid. But for several months back in 1940 and 1941, Bowling Green, Caroline County’s seat, was the unlikely home to artist Salvador Dalí, opens a new window and authors Henry Miller, opens a new window and Anaïs Nin, opens a new window.

The three were guests at Hampton Manor, which had recently been purchased by the colorful Caresse Crosby, opens a new window (who patented the first modern bra, published the first editions by T.S. Eliot and James Joyce, and was heir to the fortune of her husband, who killed his mistress and himself after their indiscretions were discovered… but hers is a story for another blog post). Crosby’s vision of an artists’ colony at the nearly 500-acre site never came to fruition, but, for a brief time, three noteworthy artistic minds of the 20th century lived and worked in her quintessentially 19th-century mansion.

Dalí, ever the eccentric, did little to endear himself to his creative colleagues during his stay. Fortunately, both Miller and Nin documented their disdain for Dalí, giving history voyeurs a glimpse into a very unusual scene from the annals of rural Virginia. That Dalí rubbed his housemates the wrong way is hardly shocking, as he was a well-known provocateur. More surprising is the fact that this trio came together in a most improbable place and, for a time, Bowling Green, Virginia, was a hotbed of modern art and literature.

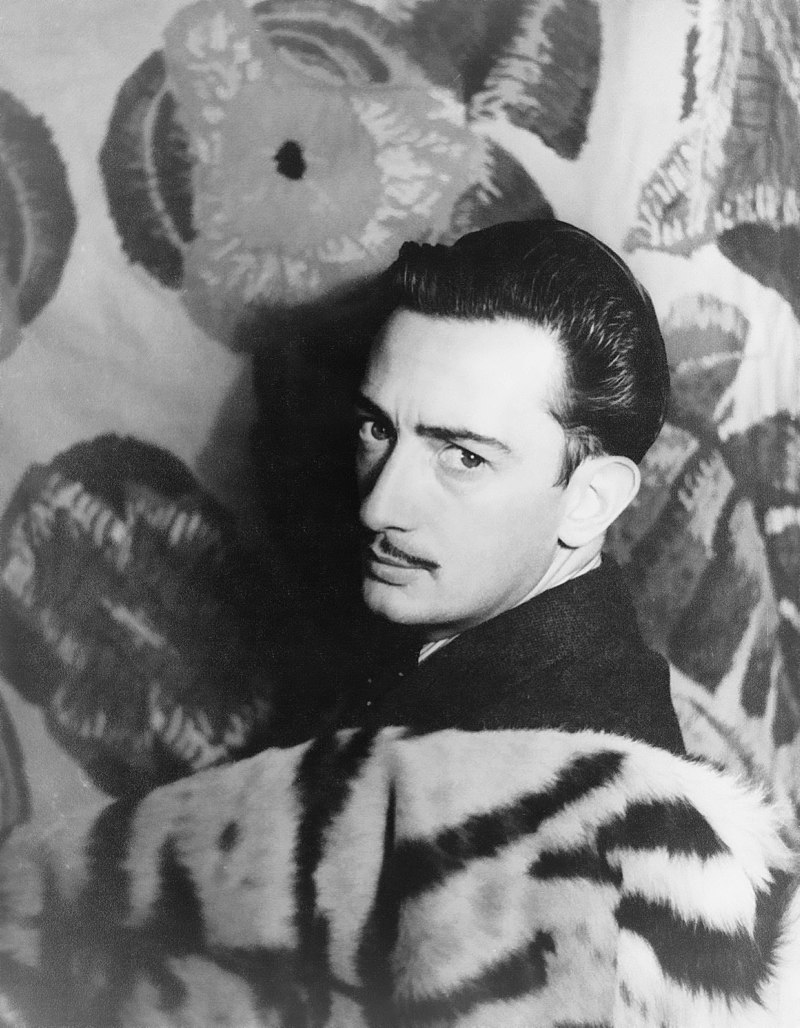

By 1940, Dalí was well-known in the art community, which is attributable to both his unique style and his penchant for self-promotion. Artistically, Dalí was a polarizing figure who was seen by some critics as a visionary genius and by others as a shameless “poseur-exhibitionist.”1 Best known for his 1931 painting featuring melting clocks, entitled The Persistence of Memory, Dalí was also a sculptor, set and costume designer for stage and screen, and a writer. Dalí worked with Disney animators on a project that languished for 58 years2 and designed an aptly odd dream sequence for Alfred Hitchcock’s 1945 film Spellbound. Always by his side was his muse and manager, Gala Dalí, whom he married in 1934 and who both provided her husband with artistic inspiration and facilitated his self-obsessed lifestyle.

During his stay in Bowling Green, Dalí was productive. He created several paintings, including Daddy Longlegs of the Evening-Hope! which features some similar imagery to The Persistence of Memory, and Slave Market with Disappearing Bust of Voltaire, which could be viewed as a mash-up of Dalí’s European mindset and the American Southern setting in which it was composed. Dalí also made the scene in Richmond, where he designed the scandalous, sexually suggestive costumes for a Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo production of Bacchanale at the Mosque. A proposal was made by Dalí and his patrons, the Reynolds family (owners of the Eskimo Pie Company and its parent company, Reynolds Metals), to erect the first statue of a woman on Richmond’s then venerable, now somewhat controversial,3 Monument Avenue.

That project, which was to have honored Captain Sally Louisa Tompkins, a Civil War nurse who ran a highly successful hospital in Richmond and was the only female officer commissioned in the Confederate Army, never made it past the idea stage. A sketch of the proposed statue shows Capt. Tompkins slaying a dragon on a base supported by a 20-foot replica of Dalí’s index finger. It was to have been rendered in pink aluminum supplied by Reynolds Metals, the corporate logo of which was an image of St. George slaying a dragon. It is hard to imagine such an outrageous design receiving the approval of city leaders. If Richmond was shocked by Dalí’s racy costume designs, which were only seen by a small number of theatergoers, it is likely that the public display of a garish pink sculpture among the staid equestrian castings of revered Civil War generals on Monument Avenue would have been seen as an affront and dominated public debate around the city and beyond—which would have pleased Dalí to no end, of course.

Back at Hampton Manor, Dalí made his presence known as soon as he and Gala moved in. As Nin recounted in her diary:

They hadn’t counted on Mrs. Dalí’s talent for organization. Before anyone realized what was happening, the entire household was there for the sole purpose of making the Dalís happy. No one was allowed to set foot in the library because he wanted to work there. Would [artist John] Dudley be so kind and drive to Richmond to pick up something or other that Dalí needed for painting? Would she [Nin] mind translating an article for him? Was Caresse going to invite LIFE magazine for a visit? In other words, everyone performed the tasks assigned to them. All the while, Mrs. Dalí never raised her voice, never tried to seduce or flatter them: it was implicitly assumed that all were there to serve Dalí, the great, indisputable artist.4

During the Dalís' stay, LIFE Magazine did, indeed, publish a profile of the Dalís in Virginia. The article includes some decidedly Dalíesque staged photos, including a portrait of Crosby and the Dalís ostensibly working on his autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, while a Hereford bull lounges on the floor of the study, and an elaborate, racially dubious tableau vivant entitled The Effect of Seven Negroes, a Black Piano, and Two Black Pigs on the Snow. Dalí also set himself to “enchanting” the grounds of Hampton Manor by floating a grand piano in a pond and submerging an unclothed mannequin to the waist. The “enchantments” were to have been open for public viewing, but the exhibit was never completed.

The “enchantment” of Hampton Manor was among Miller’s many reasons for disliking Dalí, whom he seemed to dislike both as an artist and a person. While Miller’s work, like Dalí’s, often broke free from the boundaries of the mainstream, Miller did not appreciate Dalí’s bent for self-conscious publicity and had no time for his tendency toward hyperbole. Over thirty years later, Miller still vividly recalled his contempt for him. In 1973, Miller inscribed a friend’s copy of Billy Rose’s Wine, Women, and Words, which Dalí illustrated, with a bitingly profane opinion of his former housemate that is best left unrepeated in polite company.5 Dalí’s recollections of Miller were never recorded, but their time together at Hampton culminated in a shouting match, after which Miller and Nin fled the property, never crossing paths with Dalí again.

While rural Virginia is certainly an offbeat venue for a tiff between these three cutting-edge artists, the surrealism of the scene seems fitting, under the circumstances. Bowling Green quickly returned to normal after the trio left, and today nothing remains of the visit save for the LIFE article and, perhaps, some bemused recollections of the town’s elders. All three artists eventually ended up in California, a much more traditional atmosphere for non-traditional modes of expression. Dalí later returned to his hometown in Spain, where his 1989 death failed to curtail the controversy that followed him throughout his life. In July 2017, his body was exhumed for DNA testing to determine whether Dalí had fathered a child from an illicit 1955 affair. According to the forensic doctor who opened the crypt, Dalí’s iconic mustache was perfectly intact nearly 30 years after his demise.

Editor's note: this article was published in 2018, before the statues of Confederate leaders were removed from Richmond's Monument Avenue.

1 Stephen J. Gertz, “Henry Miller Loathed Salvador Dalí (And Anaïs Nin Wasn’t Crazy About Him, Either),” Booktryst.com

2 The project was revived in 1999, and, in 2003, the short animated film Destino, based on Dalí’s original storyboards, was released by Disney.

3 A movement is afoot to remove the statues commemorating Confederate figures for which Monument Avenue is named.

4 Gertz, Booktryst.com

5 Gertz, Booktryst.com