By Dan Enos

One of the charms of Fredericksburg, especially in the downtown historic/business district, is the old-timey, small-town feel that is created by the many 19th-century structures still in use today. However, despite the fact that people have been doing business here for well over 300 years, not much of the existing downtown Fredericksburg commercial district was constructed before about 1825. As reported by Gary Stanton in his 1997 article “Alarmed by the Cry of Fire: How Fire Changed Fredericksburg, Virginia,”* in the 18th century, the dominant downtown commercial structure was a detached wooden frame building, often with a wooden chimney. Sounds quaint and picturesque, sure, but the reality was that the entire downtown district was an inferno waiting to happen. And it did happen - again and again. Between 1799 and 1823, there were at least five major fires that burned entire blocks. The largest was in 1807, and it consumed more than four blocks along what is now known as Sophia Street and Caroline Street. In fact, during those decades, just about everything burned along Caroline between Charlotte and Fauquier streets.

Of course, during the early part of the 19th century, as Americans began moving in larger and larger numbers into cities, urban fires were a problem everywhere. As college professor and local historian Edward Alvey pointed out in his 1981 study of the Fredericksburg Fire of 1807, large swaths of Boston, New Orleans, Charleston, Detroit, and Savannah were ravaged by giant fires during the 1790s. While each of these disastrous events was a tragedy in its own right, each one provided an opportunity for both renewal of the burned areas and for advancements in building and firefighting technology to prevent further calamity.

The biggest motivator in preventing fire was financial. Business owners lost entire inventories with every fire. Many who lived above or behind their commercial shops lost everything they owned. Fire departments at the time were made up entirely of volunteers (whose labor was often rewarded with beer) and, because of the time it took to reach the scene of a fire and the tremendous physical effort required to haul equipment and operate the manual pumps, their main job was often containing the fire as best they could rather than saving the burning buildings. But even after the 1807 fire devastated so many homes and businesses, city leaders still struggled to consistently maintain any kind of firefighting force and sought instead to curtail the causes of fires by passing ordinances like the one banning chimney use in fair weather - the fine for violators: $3.

Gradually, the materials used in construction in the business district began to evolve. First, slate roofs replaced wood shingles on commercial and residential buildings alike. After the 1807 blaze, new buildings were sometimes covered in earthenware tile as a protective measure. Eventually, building designs would include stone and brick facades, parapets (a vertical extension of the exterior wall of the building that can prevent flames from spreading to adjacent structures), and iron structural supports in place of wood. Gradually, the entire downtown precinct was improved, and very few commercial structures constructed primarily of wood have survived.

That old-timey feel we cherish today, when viewed through the lens of fire protection, represents a fairly sophisticated technological shift in building engineering and construction during the 19th century. Although large urban fires still commonly happened a century or so ago, whether caused by Mrs. O’Leary’s cow (see: Chicago, 1871) or by a massive earthquake (see: San Francisco, 1906), Fredericksburg circa 2018 continues to benefit from the lessons learned in the early 1800s. However, even with today's updated construction methods and firefighting techniques, fires are still a major danger; Grenfell Tower, a 24-story apartment building in London, UK, was built in 1974, renovated in 2016 - experts say faulty materials were used - and tragically burned in 2017, killing at least 79 people.

For more information on Fredericksburg’s fiery past (or any other aspect of local history), stop by the Virginiana Room, located on the lower level of the Fredericksburg Branch.

*Available through the JSTOR database or in the Virginiana Room's vertical file

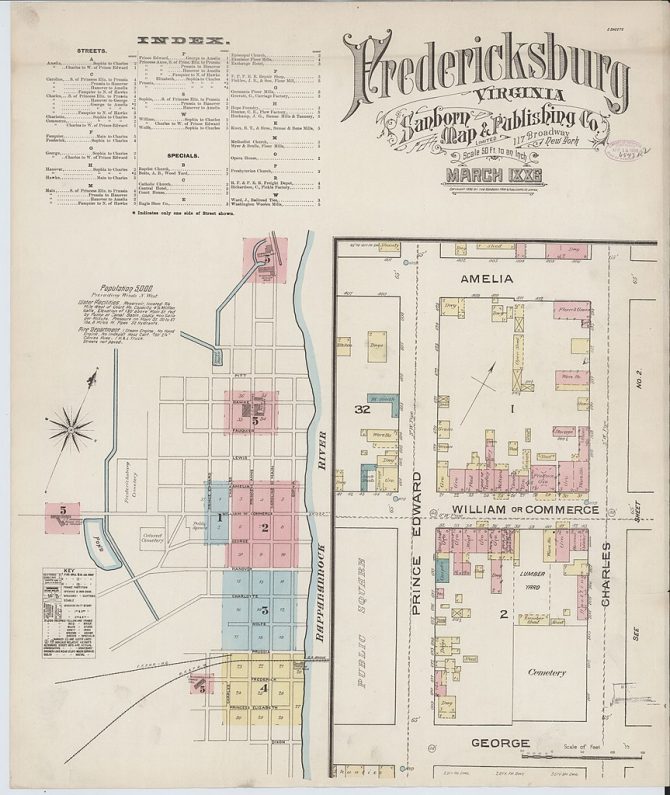

Dan Enos is a volunteer in the library's Virginiana Room. There you can trace the changes in Fredericksburg buildings using the Sanborn fire insurance maps. These maps show building footprints, building material, height or number of stories, lot lines, and building use. The Virginiana Room has maps that date back to 1886.