From the Fredericksburg Department of Tourism

During the American Civil War, Fredericksburg's geographic location drew contending armies to its environs with a deadly inevitability. The City is located on the banks of a river that served as a natural defensive barrier as well as astride a north-south rail corridor that helped keep the large armies supplied. On four separate occasions, the Union Army of the Potomac fought the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in and around the City. These clashes left over 100,000 casualties and a scarred landscape in their wake.

This walking tour will visit scenes of the Fredericksburg Campaign of November - December 1862 - the first of these encounters. The tour is divided into two parts that can be combined or walked on separate occasions, as you desire.

Part I: Fire in the Streets

On November 17, 1862, advance units of the Union Army readied the heights overlooking the Rappahannock River and the town of Fredericksburg. Within days, the remainder of this host, commanded by Major General Ambrose E. Burnside, had arrived. But Burnside would not order an advance across the river without adequate bridges, for fear that such a force could be too easily isolated and destroyed. His decision to await the delayed arrival of pontoon bridging equipment enabled Lieutenant General Robert E. Lee to concentrate his scattered Confederate forces on the heights behind the town.

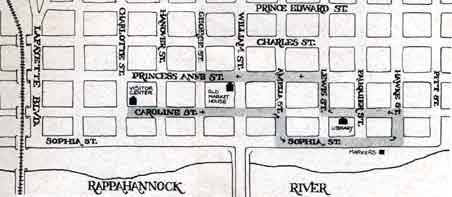

As you depart the Visitor Center, turn left and walk dawn Caroline Street. Many of the buildings you see were here during the Civil War. Turn right at Amelia Street, proceed one block, and turn left on Sophia Street. Stop when you reach the historical markers on the right, just before Hawke Street. Across the river, you will see Chatham, which served as a Union headquarters and hospital during the battle

In the early morning of December 11, Union engineers on the opposite bank began to ready their equipment to construct a bridge. Alert Confederate pickets reported this muffled activity and around 4:00 a.m. a Confederate battery subsequently broke the early morning calm by firing twice; the signal that the enemy was coming.

Brigadier General William Barksdale's Mississippi brigade took up their assigned positions along this riverbank, in cellars and other barricaded shelters. They heard the engineers begin work on extending a pontoon bridge from the opposite bank, but a heavy fog initially screened the bridge builders from these waiting riflemen. Once the Mississippians could discern the approaching bridge through the thinning mist, however, they opened fire. Some of the Union workmen collapsed onto the deck while the remainder quickly retreated to safety.

Union commanders responded by ordering their artillery to suppress the musketry coming from the town, first by directing the fire of 36 field pieces against the sheltered sharp-shooters, then by a general bombardment from 150 cannons that sent a storm of metal tearing through the town. A Confederate colonel described the scene from a vantage point beyond Fredericksburg. On the opposite bank, he saw a "line of angry blazing guns firing through white clouds of smoke & almost shaking the earth with their roar. Over & in the town the white winkings of the bursting shells reminded one of a countless swarm of fire-flies. Several buildings were set on fire, & their black smoke rose in remarkably slender, straight, & tall columns for two hundred feet, perhaps, before they began to spread horizontally & unite in a great black canopy."

Despite the bombardment, the well-protected sharpshooters persistently resumed their fire whenever the Union engineers ventured back onto the partially completed bridge to continue work. By late afternoon, with daylight rapidly slipping away, two Union infantry regiments received orders to seize the area where you are now standing to allow the engineers to complete their task. When all preparations had been made, the soldiers piled into several pontoons and rowed them quickly across the river. Barksdale's marksmen opened fire but could not hold back the approaching boats. Protected by the embankment in front of you, the Federal infantry disembarked, deployed as skirmishers, and advanced to clear the edge of town.

A soldier in the 17th Mississippi recalled the bombardment and the river crossing. "There were six men in the basement of [a] two-story house, and any one of them now living will testify to the fact that the house was torn to pieces, the chimney falling down in the basement among us; ... A few moments after the batteries opened, several regiments of Union infantry came yelling down the hill toward the river, laying hold of the boats and coming over toward where we were stationed. As they came up the bank we tried to get out at the end of the house."

The two northern regiments, 7th Michigan and the 19th Massachusetts, rushed the houses on Sophia Street and began working their way into town. Barksdale's men launched a furious counterattack against the advancing Federal soldiers and forced them back nearly to the river. Consequently, the 20th Massachusetts also crossed in pontoon boats to reinforce the shaky Union lodgement.

One soldier in the 20th later wrote that the "Michigan men made a rush at the nearest houses and took quite a number of prisoners. The orders to the whole Brigade were to bayonet every armed man found firing from a house..., but it was not of course obeyed... In fact no prisoners were taken but the few the Michigans took and the wounded who lay about struck by our shells. The 7th Michigan were deployed on the left and a short distance up the street at the foot of which we landed, and the 19th on the right, both holding houses, fences, etc., and exchanging shots with the Rebels who were a little farther back... When a good many troops had got over, we were advanced up the street...."

Follow the path of this Union attack up Hawke Street to Caroline Street.

As the New Englanders of the 20th Massachusetts charged in column up this narrow street, they passed the hard-pressed 7th Michigan sheltered in an alley, probably the one still visible to your left, halfway up the block. The 19th Massachusetts had retreated through the yards and gardens to your right. The 20th forced their way to Caroline Street, losing 97 officers and men in 50 yards of grueling street fighting. Back at the river, the Union bridge builders quickly completed one bridge and began work on another.

Additional fighting men crossed over but Burnside pushed forward only enough troops to hold what had been gained. As darkness fell, the regiments that had fought their way to Caroline Street skirmished with the Confederate defenders. The 19th Massachusetts recaptured a row of buildings on the east side of Caroline Street and engaged in a final, point-blank fire-fight with the Confederates positioned in buildings on the west side of the street.

As the last detachment of the Mississippi brigade fell back, its commander learned the advancing Federals were being led by a former classmate from Harvard Law School. Mortified at the prospect of retreating from a onetime comrade, the Mississippi officer subsequently halted his men to make a stand, jeopardizing the Confederate plan to relinquish the town. He eventually had to be placed under arrest and another officer detailed to bring out the command.

Turn left on Caroline Street and proceed two blocks to the interpretive sign in front of the Central Rappahannock Regional Library. After reading it, continue down Caroline Street to Lewis Street and turn right. Proceed up Lewis Street to Princess Anne Street and turn left. Proceed down Princess Anne Street to the old Market House which now houses the Fredericksburg Area Museum and Cultural Center.

Barksdale stationed his reserves here at the Market House and in the adjoining Market Square. From this location, he dispatched reinforcements to the town wharf area where his troops were opposing a second Union river crossing. As Union troops fought their way into town from both bridges, most of Barksdale's brigade reassembled in the vicinity of the Market House before abandoning the town.

Proceed down Princess Anne Street to George Street.

On December 12, Union troops poured across the pontoon bridges into a town where many buildings were still smoldering from the previous day's bombardment.

On December 12, Union troops poured across the pontoon bridges into a town where many buildings were still smoldering from the previous day's bombardment.

A newspaper correspondent described the wreckage: "In some cases the whole side of a house has been shot away, roofs and chimneys have tumbled in, window frames smashed to atoms, and doors jarred from the hinges." Some Northern units deployed beyond the edge of town where they skirmished with the Southern pickets. The rest of the Union striking force massed in the town to await a renewal of serious fighting.

In addition to the damage wreaked by combat action, the town suffered from a more deliberate destruction. Looting had begun the night before as infuriated soldiers who had fought through these streets released their anger. They were joined the next day by increasing numbers of troops who regarded the town as a prize of war.

One soldier recalled: "Furniture of all sorts is strewn along the streets.... Every namable household utensil or article of furniture, stoves, crockery and glass-ware, pots, kettles and tins, are scattered, and smashed and thrown everywhere, indoors and out, as if there had fallen a shower of them in the midst of a mighty whirlwind."

The war had settled harshly on the once quiet town. Endless columns of infantry and cavalry, accompanied by artillery and supply wagons, churned the streets into mud. Stacked muskets sprang up everywhere as the troops settled in to wait for the next day's assaults. Looting continued unabated, the chaos punctuated by an occasional shell whistling overhead, fired from the Confederate batteries emplaced on the heights beyond.

If you wish to continue your tour through the events of December 13, 1862, you may proceed from this point with Part II. If you wish to return to the Visitor Center, proceed down George Street to Caroline Street and turn right. Proceed two blocks to the Visitor Center.

PART II: The Assault on Marye's Heights

This brochure continues the discussion begun in Part 1. Remain standing at the point where you finished Part 1, or, if you are starting at the Visitor Center on Caroline Street, turn left down Caroline Street and proceed to George Street. Turn left on George Street and proceed to Princess Anne Street.

On the morning of December 13th, Northern troops deployed in line of battle within the confines of these narrow streets. At approximately 10 a.m., they heard the crash of artillery and musketry as Union forces attacked the Confederate lines south of town. One hour later, couriers galloped up with orders for the troops waiting in town to advance and the Union assault columns pushed forward.

On the morning of December 13th, Northern troops deployed in line of battle within the confines of these narrow streets. At approximately 10 a.m., they heard the crash of artillery and musketry as Union forces attacked the Confederate lines south of town. One hour later, couriers galloped up with orders for the troops waiting in town to advance and the Union assault columns pushed forward.

Cross Princess Anne Street and turn left. Note the Courthouse to your left. Its cupola served as a Union signal station and observation post.

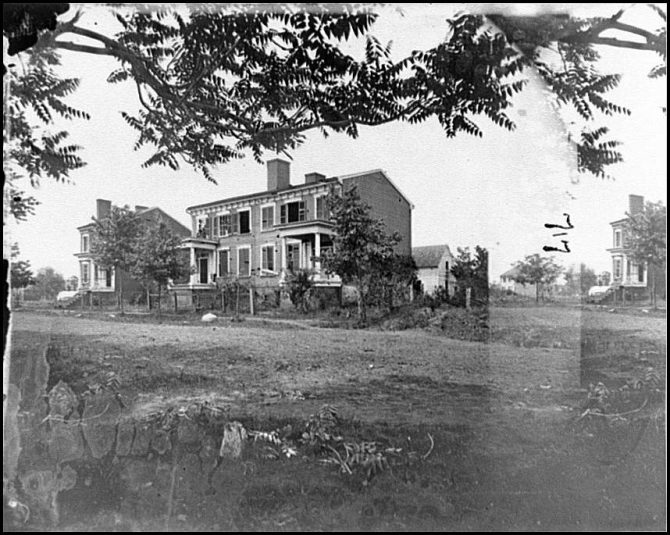

Cross Hanover Street and turn right. You are now following one of the Union army's main avenues of approach to the battlefield beyond town. Once you cross Prince Edward Street, you will see a large frame house, "Federal Hill," on the left that sits at an angle to the street. In 1862, this point marked the edge of town. Ironically, Brigadier General T. R. R. Cobb, the grandson of one of its prewar owners, commanded many of the Confederate troops who awaited the oncoming Federals. Only gardens, meadows, and a few scattered buildings were located between here and Cobb's veterans.

Once the dense columns of the Union Second Corps came into view of the rebel artillerymen, they were subjected to an increasingly accurate fire that tore through them. The Northern soldiers closed ranks to maintain the integrity of their formations and pressed on.

Continue down Hanover Street to Kenmore Avenue which, in 1862, was an open canal ditch. The advancing troops became bottlenecked at a bridge at this location and elsewhere where retreating Confederates had taken up some of the planking. The Union soldiers were forced to either gingerly cross on the stringers or wade the freezing waterway.

Cross Kenmore Avenue and pause by the embankment to your left.

The lead Union division crossed the canal and immediately deployed, protected from direct artillery and musketry by this sheltering earth. When they were ready, the first brigade of this division fixed bayonets and charged up the slope to attack the Confederate defenders beyond. As the federals topped the rise, they were met with a murderous fire which only intensified as they struggled forward over the rough and muddy ground.

Follow the Union attack up Hanover Street to Littlepage Street. The large brick house in the middle of the block (801 Hanover Street) was here at the time of the battle. There was also a cluster of now demolished buildings at the intersection of Hanover and Littlepage Street which soon developed into a Union stronghold.

When the first federal assault reached this vicinity, no other troops had yet emerged from the Confederate fire and without support, the attacking troops could go no farther. They quickly took cover in and around available houses, behind fences, and anywhere else that provided a semblance of protection.

A Union officer watched this and subsequent attacks from the vantage point of the courthouse cupola. He reported: "I had never before seen fighting like that... There was no cheering on the part of the men, but a stubborn determination... I don't think there was much feeling of success. As they charged, the artillery fire would break their formation and they would get mixed; then they would close up, go forward, receive the withering infantry fire, and those who were able would run to the houses and fight as best they could; and then the next brigade coming up in succession would do its duty and melt like snow coming down on warm ground."

Cross Littlepage Street and turn left. As you cross Kirkland Street, look to your right to glimpse the Confederate infantry position, bordered by stone walls, along Sunken Road.

Though successive waves of Union infantry were ordered into the teeth of concentrated Confederate musketry and artillery fire, the bulk of the Union artillery remained on the opposite bank of the Rappahannock River to lend support at long range. A few Union batteries, however, had been brought across the pontoon bridges and deployed on the high ground east of the canal ditch, near Federal Hill. Around 3:30 p.m.,a Federal commander ordered some of these cannons beyond the canal ditch to relieve the pressure on the hard-pressed infantry. Captain J. G. Hazard and his artillerists of Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Artillery hauled their six cannon across one of the bridges and up the slope. They unlimbered for action within 150 yards of the stone wall (probably somewhere near the intersection of Hanover and Littlepage Streets). Their fire was soon joined by that of two other batteries which also crossed the canal. These daring gunners provided a measure of close-in support, but their casualties were horrendous.

Proceed along Littlepage Street to Mercer Street. Pause beside the brick Stratton House (700 Littlepage Street) which stood quite alone in this area in 1862. As the storm of lead and jagged metal, flew around it, the house drew wounded and demoralized Union soldiers to its shelter like a magnet.

Although the land around you has been extensively developed, its contours are still evident. The slight depression extending past the Stratton house and parallel to Littlepage Street, for example, afforded some protection to soldiers lying prone. As each attack failed, this fold of ground sheltered an increasing number of soldiers. The bravery and endurance of these men became a liability, however, as the momentum of subsequent attacks was lost, not only to enemy fire, but to this obstacle of massed soldiers.

In the late afternoon, a Union officer in this vicinity observed: "The smoke lay so thick that we could not see the enemy, and I think they cold not see us, but we were aware of the fact that somebody in our front was doing a great deal of shooting. I found the brick (Stratton) house packed with men; and behind it the dead and the living were as thick as they could be crowded together. The dead were rolled out for shelter, and the dead horses were used for breastworks. The plain thereabouts was dotted with our fallen."

Turn right onto Mercer Street and follow it towards the Confederate lines until you reach Willis Street. From here you can readily see the strength of Lee's defenses. Infantry in the sunken road in front of you laid down a continuous hail of lead while artillery on the heights behind them raked the field with a devastating fire. Turn left on Willis Street and follow it to Lafayette Boulevard. On December 13, 1862, this area was strewn with dead and dying soldiers, whose bodies marked the farthest advance of the Union attacks. Turn right on Lafayette Boulevard.

In the gathering twilight, elements of the Union Ninth and Fifth Corps advanced over the broken fields to your left and rear against that section of Marye's Heights directly in front of you. Confederate volleys lit the field as if by sheet lightning and these final attacks, like the previous ones, soon collapsed.

Continue up Lafayette Boulevard to the National Park Service Visitor Center. Gain a fuller understanding of the events of December 1862 by availing yourself of the excellent exhibits and literature there. This brochure will resume its directions to guide you back to the City Visitor Center when you reach the Kirkland Monument, which is on the Park Service walking trail.

Around midnight of December 13, Union reserves moved up to relieve those soldiers who had survived the daylight fighting. The night turned bitterly cold as a north wind swept the field. Under the cover of darkness, stretcher bearers searched for the wounded, but many soldiers perished and stiffened before they were found. The dead were stripped of their clothing by ill-clad Confederates as well as by Union troops who had been ordered to leave their knapsacks and overcoats in town. Each soldier passed the miserable night as best he could, the experience etching itself differently in their respective memories. One man remembered sleeping next to several corpses while another recalled the sound of a window shutter banging on a nearby building all night.

Proceed down Kirkland Street to Littlepage Street.

The relieving troops took up their position in the depression parallel to Littlepage Street. At daybreak, the Confederates subjected these exposed newcomers to a horrible, day-long ordeal of sniping and sharpshooting. The cold and muddy soldiers had no option but to hug the ground, barely sheltered by the earth and frozen corpses. When the sun finally went down, the troops received welcome orders to retreat.

A soldier from Maine described the return march: "We had to pick our way over a field strewn with incongruous ruin; men torn and broken and cut to pieces in every indescribable way, cannon dismounted, gun carriages smashed or overturned, ammunition chests flung wildly about, horses dead and half dead still held in harness, accouterments of every sort scattered as by whirlwinds."

Follow the retreating troops back down Hanover Street. After you cross Kenmore Avenue, bear to the left and follow George Street back to Princess Anne Street.

A Union officer wrote the following account of the withdrawal: "We marched past the court-house, past churches, schools, bank-buildings, private houses, all lighted for hospital purposes, and all in use, though a part of the wounded had been transferred across the river. Even the door-yards had their litter-beds, and were well filled with wounded men, and the dead were laid in rows for burial. The hospital lights and camp-fires in the streets, and the smoldering ruins of burned buildings, with the mixture of the lawless rioting of the demoralized stragglers, and the suffering and death in the hospitals, gave the sacked and gutted town the look of pandemonium."

During the night of December 15-16, under cover of a heavy rain, the Army of the Potomac withdrew across the Rappahannock River. The Battle of Fredericksburg was over.

Follow George Street downhill to Caroline Street and turn right. Proceed two blocks to your starting point at the Visitor Center.

Fredericksburg Department of Tourism

visitfred.com

706 Caroline Street

Fredericksburg, VA 22401

(703) 373-1776 or 1-800-678-4748

"This publication is funded in part by a grant from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior through the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. The contents and opinions of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. This program received funds from the National Park Service. Regulations of the U.S. Department of the Interior strictly prohibit unlawful discrimination in the departmental Federally Assisted Programs on the basis of race, color, national origin, age or handicap. Any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of Federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, P.O. Box 37127, Washington, D.C. 20013-7127."