The huge boulder rolled deliberately in the middle of the road was the first sign of trouble. On May 11, 1889, along a dusty trail in Arizona, an unlikely bunch of desperadoes made off with $28,000 in gold from U.S. Army Paymaster Major Joseph Washington Wham. Buffalo Soldiers from the 24th Infantry were part of the 12-man escort that would go down fighting that day.

The huge boulder rolled deliberately in the middle of the road was the first sign of trouble. On May 11, 1889, along a dusty trail in Arizona, an unlikely bunch of desperadoes made off with $28,000 in gold from U.S. Army Paymaster Major Joseph Washington Wham. Buffalo Soldiers from the 24th Infantry were part of the 12-man escort that would go down fighting that day.

A buckskin-clad bandit opened fire on the wagon train from his advantageous position on the heights. The soldiers grabbed their guns, stored in the second wagon. Some were able to take cover, but others, such as Sergeant Benjamin Brown, were struck quickly by the hail of bullets coming from the other bandits, estimated to be between 12 and 15 in number. This didn't mean the soldiers stopped resisting the onslaught.

On the contrary, Major Wham stated that Sergeant Brown, a native of Spotsylvania County, Virginia, "made his entire fight from open ground." Brown's Medal of Honor citation reads in part that "although shot in the abdomen …did not leave the field until again wounded through both arms."

Corporal Isaiah Mays, another Buffalo Soldier, was also awarded the Medal of Honor. Near the end of the gun battle he, without the knowledge of Major Wham, "walked and crawled two miles to Cottonwood Ranch and gave the alarm." Brown and Mays were the only African American infantrymen to receive the Medal of Honor for bravery in the frontier Indian Wars.

Other soldiers cited for bravery, receiving the Certificate of Merit, included Hamilton Lewis, Squire Williams, George Arrington, James Wheeler, Benjamin Burge, Thomas Hams, James Young, and Julius Harrison. These men were from the 10th Cavalry and 24th Infantry, and all were Buffalo Soldiers.

Wham, his clerk, and the soldiers were ultimately forced to withdraw and the robbers succeeded in making off with the payroll, amounting to $28,345.10. A female gambler named Frankie Campbell was ordered to stay on hand to nurse the severely wounded, including Benjamin Brown.

The money was never found, although suspects were brought to trial. Quite possibly, a combination of racism and local politics prevented justice being done. While the men were charged with stealing the payroll, they were never brought to trial for the shootings. All the suspects were acquitted although some of the African American witnesses testified against them by name. Probably the most exhaustive book written on the robbery in modern times is Ambush at Bloody Run: The Wham Paymaster Robbery of 1889: A Story of Politics, Religion, Race, and Banditry in Arizona Territory, by Larry D. Ball. A quicker account focusing on the suspects can be found online at True West magazine's site.

Aftermath

The Committee on Military Affairs of the U.S. House of Representatives, after examining the evidence, stated that "the fact that the President ... has seen fit to award certificates of merit and medals of honor to the members of Major Wham's escort . . . is the highest evidence of the fact that they displayed unusual courage and skill in defense of the Government's property." Furthermore, the committee concluded, "all the evidence . . . shows conclusively that all was done by Major Wham and his brave little escort that men could do to project the Government's property…."

About Benjamin Brown

The son of Polly and Henry Brown was born about 1859 in Spotsylvania (Spottsylvania) County, Virginia. He entered military service at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and retired in 1904. During the time of the Wham robbery, he and his troop, Company C, 24th U.S. Infantry, were stationed at Fort Grant. He never fully recovered from his wounds and carried one of the bullets inside his body until his death on December 5, 1910 at Soldier's Home in Washington, D.C. You can read about him on the National Park Service's website.

Who Were Those Buffalo Soldiers?

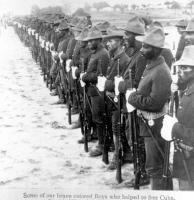

Although several African American regiments were raised during the Civil War to fight alongside the Union Army (including the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and the many United States Colored Troops Regiments), the "Buffalo Soldiers" were established by Congress as the first peacetime all-African American regiments in the regular U.S. Army.

Buffalo Soldiers is a nickname originally applied to the members of the U.S. 10th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army, which was formed on September 21, 1866 at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The term eventually encompassed these units:

U.S. 9th Cavalry

U.S. 10th Cavalry Regiment

24th Infantry Regiment

25th Infantry Regiment

The all-African American units began to be disbanded when President Harry Truman integrated the U.S. military by executive order in 1948, but the last all-African American unit was not abolished until 1954.

As for the historic Buffalo Soldiers, the 24th Infantry, Sergeant Benjamin Brown's own outfit, was the last to see combat—during the Korean War. The 24th, like most of the rest of the historic units, disbanded in 1951. Their soldiers were absorbed into the ranks of other outfits.

The history of the Buffalo Soldiers is a fascinating one. The Central Rappahannock Regional Library owns these resources that tell much more about the Buffalo Soldiers' history:

- Black Soldiers in Jim Crow Texas, 1899-1917 by Garna L. Christian

- Buffalo Soldiers, starring Danny Glover (Streaming video)

- The Buffalo Soldiers of Westmoreland County, Virginia by Daisy Howard-Douglas

- Fighting for America: Black Soldiers, the Unsung Heroes of World War II by Christopher Paul Moore

- The Legend of Cathay Williams, Female Buffalo Soldier by Daisy Howard-Douglas

- On the Trail of the Buffalo Soldier: Biographies of African Americans in the U.S. Army, 1866-1917 compiled and edited by Frank N. Schubert

- Under Fire with the Tenth U.S. Cavalry by Hershel B. Cashin.

For Younger Audiences

- Buffalo Soldiers by Catherine Reef

- Cathy Williams, Buffalo Soldier by Sharon K. Solomon