To the Spaniards, he was known as young Litlpese. Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette knew him as the charming Little Peche. In Russia, to Catherine the Great and her favorites, he was the clever and ambitious Litlpaz. The doomed monarch, Stanislas Augustus of Poland, knew him as his loyal Litelpecz. Whatever the name, this often penniless Virginian's brilliant intellect and exquisite manners won him entry into the chambers, gaming tables, and salons of the last decades of Europe's Age of Enlightenment.

The Young and Orphaned Genius

He was born to live the simple, indebted life of a colonial gentleman. His family came to Virginia from England in 1663 and established a plantation called South Wales, four thousand acres at the confluence of the North and South Anna rivers of the Pamunkey in Hanover County. Lewis' father, James Littlepage, married a lady of Spotsylvania's Bel-Air plantation, Elizabeth (Betty) Lewis. She was the daughter of a wealthy lawyer and burgess, Zachary Lewis II. This Lewis family was not related to George Washington's in-laws, but they were certainly respected in the community. James Littlepage would go on to become a member of the House of Burgesses in 1764. Before his death in 1766, he had amassed considerable debt, so much so that he walked about armed to avoid being taken to jail by the local sheriff.

Nonetheless, upon his death, there were some holdings to be distributed amongst his kin, although South Wales had to be sold to pay the family debts. The large family (young Lewis had one sister, and James Littlepage had five children from a previous marriage) moved in with Betty's brother. Betty married again in 1774, this time to Lewis Holladay of Belle Fonte (Bel Font) on Northeast Creek. Her new husband became a soldier in the Spotsylvania militia and distinguished himself at the Battle of Camden. Lewis' mother was 41 when she married Holladay, who was 23.

Within a year of his mother's marriage, twelve-year-old Lewis Littlepage was packed off to Louisa County to live with his mother's youngest brother, Benjamin Lewis, and his wife. They, in turn, sent him to live with the Smiths at Walnut Grove where he learned from the family's tutor, the Reverend Mr. Hall of Trinity Parish. Young Lewis so disliked the "peevish and ill-tempered pedagogue" that he ran away from home to live with his half-brother. Clearly, however, he was a gifted student, for his poetry on the new national leaders of the American Revolution appeared in the Virginia Gazette, and his translation of an ode in the First Book of Horace won him acclaim in national literary circles.

Benjamin Lewis, now his guardian, decided that rather than return his nephew to the peevish tutoring of the Reverend, he would send him to the College of William and Mary. He arrived in the spring of 1778 and found the town full of prosperous relatives. An uncle (his mother's sister's husband), George Wythe, would soon start the first law course offered in the new country in Williamsburg. His half-brother, Carter Littlepage, had won a bid to refurnish the Governor's Palace for the first American governor of the Commonwealth. Patrick Henry, from Hanover County, was also a family friend and business associate. Even with all of these gleaming family connections, Littlepage still lacked the funds to pursue his education. Fortunately, he won, by virtue of his abilities in Latin and Greek, a Nottoway scholarship to the College.

The Revolutionary War came to the Williamsburg area in May of 1779. On May 13, the British gunboat Rainbow bombarded young Major Thomas Mathews' (Mathews County was later named for him.) men, sending them to the shelter of the Dismal Swamp. In a nearby area, volunteers from the College of William and Mary held positions. Lewis Littlepage was among them, and, in his eagerness, got captured by the enemy and was then released. Despite a pleasant social life at college, sixteen-year-old Lewis began to think in terms of moving on and away to better acquire useful experiences and a more glorious reputation. A family friend, Thomas Adams, recommended him to the recent president of Congress, Mr. John Jay of New York. Jay had just accepted the post of first Minister Plenipotentiary to the Court of Spain. In his recommendation, Adams spoke of "a young gentleman whose talents and disposition merited better opportunity." Jay accepted the young man and offered him board and lodging if he could find his way to Spain. Benjamin Lewis, still the boy's guardian, was persuaded to provide transportation money and a very basic allowance, although he was himself in serious financial difficulties at the time.

An Expensive Course in Diplomacy

Due to bad weather during the voyage, the ship arrived not in Spain but in France. He found himself in Nantes, hundreds of miles from Spain. Lewis' achievements in Latin did not help him in France. He spoke not a word of French, but he used the intervening months while arranging travel and recovering from malaria to learn it and absorb much of France's customs and history. Indeed, illness would plague Lewis throughout his life, often altering his grueling travel schedule. Unfortunately, no portrait of Littlepage exists, but the trunks of fine clothes, including court dress, that he eventually brought back to Virginia indicate that Lewis was only a few inches over five feet tall and slender in build. Particularly in his youth, his good looks and charm were noted in correspondence by several ladies at European courts.

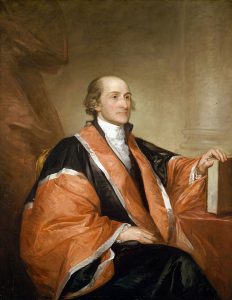

Upon arriving in the Spanish capital, Lewis entered John Jay's household, unaware that there were forces at play that would put him into conflict with the man who ought to have been his revered benefactor. John Jay, later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, was in many ways Littlepage's opposite. He was a tall, thin man who had little enjoyment for the cultured pleasures of music, theater, or fine dining. It was another Virginian, James Madison, who said of John Jay, "he had two strong traits of character, suspicion and religious bigotry."

Jay's brother-in-law, Henry Brockholst Livingston, was altogether a different sort of fellow. He had an explosive temper, greatly enjoyed companionable drinking, telling tall tales about America, and had a broad sense of humor. He found Lewis to be clever and capable of helping John Jay in all particulars. He and Littlepage became life-long friends. Eventually, Livingston would also become a Supreme Court Justice.

William Carmichael, Jr. was the Secretary of the Legation, by congressional appointment. He was clever at diplomatic maneuvering and, unlike John Jay, wise in the ways of the world. Carmichael performed his role as intelligence gatherer beautifully by becoming a vital part of the Madrid society, becoming a close associate of the French Ambassador Montmorin, and making a positive impression on the Prime Minister of Spain. Livingston, and eventually Lewis Littlepage, would come to be charmed by him, and, certainly took note of his methods of information gathering. He and Jay were constantly at odds and, over time, Littlepage found himself being pulled into the fray.

Littlepage enjoyed going on the town at night, although he was embarrassed when word of his dalliances reached John Jay's ears via Carmichael. Lewis reported to Jay that Carmichael was attempting "to seduce me into pursuits which would lessen your good opinion of my honor and my morals."

As to the young man's rising expenses, Jay had agreed to advance him some cash with the understanding that Benjamin Lewis would cover his nephew's debts, but when Littlepage wanted to volunteer for a Spanish military expedition to Buenos Aires, Jay was livid. This kind of experience would prepare him for a military life when he had been specifically entrusted to prepare Littlepage for a life of civil service. Littlepage persisted and wrangled an invitation to join the expedition from Florida Blanca, the Spanish prime minister who recommended to the Minister of War that "Don Luis Littlepage, distinguished young man from the American Provinces who is here to learn the language and to study" be allowed to join them. Jay promptly wrote a letter to Blanca in which he recommended Littlepage's character but washed his hands of all responsibility for the young pup, although he still took an interest in his financial affairs.

In the following months, Littlepage would have many adventures in his early quest for prestige, including being on board a gunboat during the Duke of Crillon's ill-fated siege of the English-held Gibraltar in 1783. All this dashing about with a keen desire to be noticed racked up sizeable debts owed to John Jay, who was keeping careful accounts. Indeed, a quick glance at standard reference works makes note only of Jay's and Littlepage's bitter feud that enlivened the newspapers of Philadelphia with its parties' venomous notes during Littlepage's brief sojourn in 1785. At the height of their mutual fury, Littlepage, once more immersed in his role of the Virginia gentleman-- among whom debts were common and assaults on honor held far more serious consequences, challenged the older man to a duel. Jay refused his challenge, leaving his former protegee with little recourse but to return to the Continent. He had come back, hoping to be given a good post with the new government, but found his hopes dashed - although he did manage to make a good impression on George Washington who carefully noted in his diary, "This Captn. Littlepage is an extraordinary Character."

Indeed, by the time of his return, Littlepage, although deeply in debt, had found that friendship was a kind of coin which he could have at hand readily by aid of his engaging personality and clever wit. He had become close friends with that bon ami to the American cause, General Lafayette. Littlepage had also met the man who would have the most influence on his future: Stanislas August Poinatowski, the last King of Poland.

This charming, handsome, and scholarly individual was chosen for the throne mainly because of his position as one of Catherine the Great's early favorites. He would prove in time to be as much a father figure as an employer for Lewis Littlepage. He trusted the young American implicitly and made him a court chamberlain. Soon Littlepage would be sent as the King's envoy to the Russian Court to negotiate a treaty. For a time, the Czarina "borrowed" him from Stanislas to command several ships in a naval attack against the Turks.

He was part of a contingent led by another American in search of glory after the Revolution, John Paul Jones. Admiral Sir John Paul Jones led the Russian Navy to a victory, but ultimately lost favor at Catherine's court when he could not find common ground with yet another of the Czarina's favorites, the Prince de Nassau-Siegen. Littlepage stood by his fellow countryman and advised him to take a more diplomatic approach to his problem. He attempted to reconcile the two admirals, but to no avail. In quick order, both Jones and Littlepage would be personae non gratae at the Russian Court.

Stanislas sent him to France and Spain also, in hopes of gaining support for his failing kingdom. In addition to her financial woes and weakly constructed government, Poland was plagued with two aggressive neighbors, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the usually friendly if possessive Russians. It seemed little could be done to shore up the crumbling government, but at last, in May of 1792, a rise of nationalistic sentiment led to the formation of a republic with a new and popular constitution. It seemed the fires of the French Revolution were only causing a gentle warming in Poland's capital as the city council toasted the King:

- "Vive le premier Citoyen! Vive l'amie des Hommes!"

The rejoicing would be short-lived. Within five days, two Russian armies crossed the frontiers of the republic as the Imperial Court asserted a right to take an active interest in the political affairs of Poland. Littlepage estimated the troops' number to be 120,000 men. He was quickly drawn into Poland's defense, being made Aide-de-Camp General to the King, with the rank of major general. Despite the people's desire for more self-rule and the best diplomatic efforts of everyone, including Littlepage, the King decided that by not giving way to Catherine's will, he would inevitably cause the partition of Poland. He asked for an armistice and received one. On August 17, 1792, Russian troops entered Warsaw.

Loyal Friends

Throughout these troubles, the King never forgot Littlepage. He visited his sickbed and wrote a letter of recommendation for "Sir Louis Littlepage" to President Washington. When Littlepage recovered, he served Stanislas however he could, diplomatically or militarily. He did not forget his other friends. Though chronically short on money himself, he sent General Lafayette's wife, Adrienne, 1,000 ducats to help her upon her release from imprisonment during the French Revolution.

Despite everyone's efforts, the partition of Poland became a reality when Prussia, too, took an interest in the doomed country's affairs. In 1794, a Polish hero of the American Revolution came home to lead his countrymen in a new foray for freedom. Thaddeus Kosciuszko ("kush-choos-ko") proclaimed "The Act of Insurrection," a document heavily influenced by the American Declaration of Independence. Thousands of people, nobles and peasants alike, signed this document. When the scythe-bearing Polish peasantry under Kosciuszko's command defeated a larger Russian force armed with artillery, Kosciuszko, though born a noble, put on the white peasant's cloak as an emblem of solidarity, and a national uprising was born.

Bloody battles in the streets of Warsaw left corpses everywhere in the wake of the mob's fury. A Russian general confided to Littlepage that his troops were scattered, and Littlepage estimated the number of Russians slaughtered as 10,000. He refused to leave although it was clear that the fighting wasn't truly over:

-

Since in insurrections people use reason only after they have fought, my friends advised me to withdraw. I refused to listen to such counsels and I should refuse them again in the same situation. Honor, gratitude and duty obligated me not to abandon the King, from whom I had accepted benefits and consequently to whom my life belonged.By a shameful flight I should have placed myself in the same class with those vile Court insects who buzz about the throne as long as they see chances of prosperity shining there but who take wing at the approach of a storm.

- It would all be over when the brilliant Russian commander Suvorov got his orders to proceed to Warsaw. Suvorov was known to Littlepage from his days at the Russian Court. This military genius lacked the beauty of his Polish counterpart, but his small, broken, and aged frame had the experience and the manpower to take Poland. His troops were well-trained, but due to the bloodbath of the earlier insurrection, Russian tempers ran high. Despite their orders, his troops began to fire on the Polish citizenry of Praga. When Suvorov saw what was happening, he sent a staff officer to urge all civilians to take refuge in the Russian encampment, but few of them made it there safely. Fierce fighting resulted in thousands of casualties on the Polish side and only a few hundred for the Russians.

Suvorov's peace demands after Praga were a better bargain than the Poles expected. They accepted his terms, which included some protections for the citizens and rules of conduct for the Russian Army. The way to Warsaw was now clear.

Lewis Littlepage spent the next six and a half years in a twilight state, roaming the courts of Europe, and ever continuing his efforts on behalf of Stanislas. He was still Chamberlain to an absent and powerless King and did what he could to keep him informed of political affairs, wherever he was. While other leaders in the revolution were killed, Littlepage was spared, probably because of his previous services to Russia, both military and diplomatic. Catherine now declared that she was responsible for Stanislas' financial commitments, including those owed to Littlepage. It would take many years and assumption of the throne by her son, Paul, to finally make good those debts.

At Home at Last

When Lewis Littlepage returned to Virginia in October of 1801, he had reached his goals of fame and fortune, but what a winding path he had chosen! Always the charmer, usually in debt, and clever enough to be useful to the monarchs of Spain, Poland, and Russia, he returned to Spotsylvania with sufficient funds - thanks to his benefactor Stanislas who finally died in 1798 - to take on the role of a country gentleman. He was ill unto death, a fact of which he was well aware, and finally tired of court intrigue.

He decided, after careful examination of his relatives, that his younger half-brother, Waller Holladay, should get the bulk of his fortune. Although fond of his older brother Carter, who shared his propensity for debt, he recognized that Waller was the steadiest of the lot and would take excellent care of their mother. Lewis Littlepage died in Fredericksburg on Monday, January 19, 1802, not quite nine months after his return to America. At his request, his papers -- excepting his Order of Knighthood and other decorations - were destroyed.

An all too brief obituary appeared in the July 20, 1802 issue of the Virginia Herald:

- "...General LEWIS LITTLEPAGE departed this life in this town yesterday evening in the 40th year of his age.--He was appointed first Confidential Secretary in the Contingent of Stanislas Augustus, late King of Poland, in March 1786 (?) and remained in that office until the subversion of that unhappy empire."

Waller Holladay buried his half-brother in the Masonic Cemetery in Fredericksburg which may be visited today. His tombstone's inscription reads:

- Here lies the body of Lewis Littlepage ... Honoured for many years with the esteem and confidence of the unfortunate Stanislas Augustus, King of Poland, he held under that monarch, until he lost his throne, the most distinguished offices. He was by him created Knight of the Order of St. Stanislas; chamberlain and confidential Secretary in his Cabinet; and acted as his special envoy in the most important negociations. ...

Waller Holladay married shortly after his brother's death and had thirteen children, the eldest of whom was named Lewis. He used his new fortune to build a fine house in Spotsylvania County which was known for a time as the Littlepage Inn.

Author's Note: most of the material in this sketch is derived from the fascinating book, The King's Chevalier by Curtis Carroll Davis. Complete bibliographic information is listed below.

Resources on Lewis Littlepage at the Central Rappahannock Regional Library

Lewis Littlepage by Nell Holladay Boand.

"A Not-So-Innocent Virginian Abroad: Lewis Littlepage, Poet, Statesman, Soldier of Fortune," by James H. Bailey, Virginia Cavalcade Volume 2, Number 2, Autumn 1952, p. 17.

At the University of Mary Washington's Simpson Library

The King's Chevalier; A Biography of Lewis Littlepage, by Curtis Carroll Davis. New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1961. Includes an extensive bibliography.