Lake Anna State Park is a favorite local destination for campers, boaters, and families who just want to spend a summer day at the lakeside beach. For most of us, the way to the lake runs down Lawyers Road. These days, there’s not much to take in with the view from this one-lane road, which passes through as quiet a stretch of Spotsylvania countryside as remains in the 21st century. But in centuries past, the western part of the county was the scene for tribal wars, enslaved laborers, religious awakenings, whiskey barrel politics, gold mining, and Civil War armies on the march.

Tribal Territory

Before the coming of the Europeans, the Piedmont land in this part of Spotsylvania was mostly claimed by the Manahoac people, part of the Siouan tribal culture. They warred with the neighboring Powhatan people, part of the Algonquian culture, who mainly inhabited the Tidewater area. They had mostly disappeared by the early 1700s and are believed to have moved southwest to merge with the Saponi who visited with Virginia Governor Alexander Spotswood at Fort Christanna in 1716. The fort, located in what is now Brunswick County, was overseen by the newly-formed Virginia Indian Company, which had a monopoly on trade. They were there to protect the new settlers, but the Company also set up a church school for the American Indian children. When the Virginia Indian Company lost its charter only a few years later, the fort lost its support, and the American Indian school was moved to Williamsburg, where it occupied a building on the College of William and Mary’s campus.

Before the coming of the Europeans, the Piedmont land in this part of Spotsylvania was mostly claimed by the Manahoac people, part of the Siouan tribal culture. They warred with the neighboring Powhatan people, part of the Algonquian culture, who mainly inhabited the Tidewater area. They had mostly disappeared by the early 1700s and are believed to have moved southwest to merge with the Saponi who visited with Virginia Governor Alexander Spotswood at Fort Christanna in 1716. The fort, located in what is now Brunswick County, was overseen by the newly-formed Virginia Indian Company, which had a monopoly on trade. They were there to protect the new settlers, but the Company also set up a church school for the American Indian children. When the Virginia Indian Company lost its charter only a few years later, the fort lost its support, and the American Indian school was moved to Williamsburg, where it occupied a building on the College of William and Mary’s campus.

The Lore of Lawyers Road

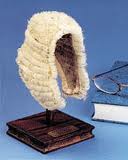

Lawyers Road traces its name back to the 18th century and a pair of lawyers by the name of Lewis. The Lewis family had several branches in our area, including the Lewises of what became known as the Kenmore Plantation, the Hanover County Lewises and the Lewis family of Albermarle, which intermarried with the Jeffersons. As to how the earliest Lewis arrivals to Virginia shores are interrelated and from whence they came, that is a matter of speculation well-discussed in the opening chapter of The Family of John Lewis, Pioneer.

In any event, there were many Lewis family members in the western part of Spotsylvania. Wealthy Zachary Lewis (1702-1765) of nearby “Bel-air” plantation was a burgess (1757-58, 1758-61), a church vestryman for St. George’s parish, and an attorney.

In any event, there were many Lewis family members in the western part of Spotsylvania. Wealthy Zachary Lewis (1702-1765) of nearby “Bel-air” plantation was a burgess (1757-58, 1758-61), a church vestryman for St. George’s parish, and an attorney.

Zachary Lewis served as the King’s attorney and was part of a partnership which acquired vast tracts of land on the New and Clinch rivers. He represented the King’s interests and in 1737 brought the Court’s attention to certain colonists who “did keep unlawful and tumultuous mootings and meetings tending to rebellion, and ask the court to take order thereon, whereupon the court ordered that the sheriff take such person into custody, till they give security for appearing at next term of court and show cause why they have unlawfully assembled.”* The malefactors were brought into custody and begged the court’s forgiveness, but it was clear that, decades before the Revolution, the seeds of discontent were already thriving.

He and his son, John Lewis (1729-1780) would take Lawyers Road (Route 601) on their way to serve at the Orange County Courthouse. For a time he also traveled with his associate and eventual son-in-law, George Wythe, who would later be elected a burgess and later still be the first Virginian to sign the Declaration of Independence. George Wythe also gave the first signature on Patrick Henry’s law license, having administered part of his bar exam. It is interesting to note that future firebrand Patrick Henry and John Lewis, son of the King’s attorney, were close friends.

In addition to being King’s attorney, Zachary Lewis also ran a plantation, worked by enslaved people. The western settlers were not the only ones in open rebellion, as this legal note attests:

May 18, 1742.

Upon Consideration of the Petition of Zachary Lewis, praying an Allowance for his Negro Man Sacco, who murdered his Overseer; and afterwards, to avoid the Punishment of the Law, hanged himself;

Resolved, That the Allegations of the said Petition are true: And that the said Zachary Lewis ought to be allowed, for the said Negro, Forty Pounds Current Money, by the Public.H.R. McIlwaine, Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1742-1747, 1748-1749. (Richmond, 1909), pp. 27.

This extreme act of rebellion was not an isolated incident. A few years later in 1746, Zachary Lewis, again acting as King’s attorney, brought before the court an instance of purported poisoning. Eve, an enslaved woman belonging to Peter Montague of Orange County, was convicted on August 19, 1745 of poisoning her owner on August 19, 1745. Montague lingered until finally dying on December 27. Eve pled not guilty, but, during her trial, witnesses brought testimony against her. She was found guilty and sentenced to be “drawn upon a hurdle to the place of execution and there burnt.” It was the last recorded case of a woman being burnt in the colony.*

Colonel Zachary Lewis: Aide to George Washington and Jeweler

Zachary Lewis, the patriarch, was a firm believer in the strictures of colonial rule, but his son, also named Zachary (1731-1803), would become part of the rebel cause as would his other son, John. Zachary the younger is said to have studied at the College of William and Mary along with Thomas Jefferson (whom his brother-in-law Wythe would later tutor in law). During the French & Indian War, young Zachary (1731-1803) became part of George Washington’s command at Old Fort Cumberland. Later, he would again be at Washington’s side during the American Revolution. This did not sit well with his wife who was a Tory sympathizer to the end of her days.

In the years between the French & Indian War and the Revolution and afterward, Colonel Zachary Lewis seems to have kept a small business in repairing watches. This was most unusual during a time when the prevailing class structure rather strictly delineated acceptable occupations for gentlemen, such as lawyering, doctoring, soldiering and running plantations. But a sketch of Colonel Lewis’ career as a craftsman does exist in James Biser Whisker’s Virginia Clockmakers and Watchmakers, c. 1660-1860, and a court record of John Marshall’s accounts clearly shows that on February 10, 1780, Lewis was paid five pounds—a large sum—to repair a watch.

Nearly a hundred years later, many descendants of the colonel gathered at the family home Bel-air to reminiscence. It is recorded in the publication The Lewis Congress that some still remembered how Colonel Lewis would pace the upstairs study, toying with some mechanical problem. Colonel Lewis’ account book for his business can be seen at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s library.

Preachers and Teachers and Diplomats

One of Colonel Zachary Lewis’ sons, John Lewis (1784-1858), ran a young men’s preparatory school at Bel-air, later known as the Llangollen school. During the War of 1812, John led a troop of Spotsylvania Cavalry (Second Regiment, Second Division, Virginia Militia) on patrol on the banks of the Potomac River. John’s elder brother, Richmond Lewis (1774-1831), also served in the war as a surgeon. In addition to being a soldier and a teacher of Latin, English and mathematics, John was also an author, penning "Analytical Outlines of the English Language," Richmond, 1825 and "Tables of Comparative Etymology and Analogous Functions," Philadelphia, 1828. In 1832, John Lewis and his family migrated to Woodlake, Kentucky.

Colonel Lewis’ youngest son, Addison Murdock Lewis (1789-1857), set aside his Greek school texts to study the ways of God as taught by a convert to the Baptist faith, an older enslaved man named Morgan who had originally lived at the home of Addison's grandfather Zachary, the King’s attorney. This turn of events shocked Addison’s Tory mother, who is reported to have tried to have another son change Addison’s mind. But that son advised the widowed Mrs. Colonel to leave him alone and let him go his own course.

Colonel Lewis’ youngest son, Addison Murdock Lewis (1789-1857), set aside his Greek school texts to study the ways of God as taught by a convert to the Baptist faith, an older enslaved man named Morgan who had originally lived at the home of Addison's grandfather Zachary, the King’s attorney. This turn of events shocked Addison’s Tory mother, who is reported to have tried to have another son change Addison’s mind. But that son advised the widowed Mrs. Colonel to leave him alone and let him go his own course.

Addison Lewis left the more socially prominent Episcopal Church in 1808 and became a church messenger, serving at the Gold Mine Church in adjacent Louisa County in 1809 and continuing on there for 20 more years. He, too, migrated to Kentucky with his family in the 1830s, having spent the 1810s and 1820s traveling through Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana, and Missouri, preaching and organizing churches.

The Lewis family was certainly prolific in the region. Indeed, the part of Rt. 601 that continues after the intersection with Courthouse Road (Rt. 208) is called Lewiston Road. The Lewis descendants intermarried with the Holladay, Scott, Waller, and Littlepage families, among others.

On a side note, Lewis Littlepage, a grandson of the patriarch/King’s attorney Zachary Lewis and a nephew to Colonel Zachary Lewis, served as an American diplomat and advisor to the last Polish king. Never married, he left his fortune to his half-brother, Waller Holladay, who used part of the money to build a fine house.

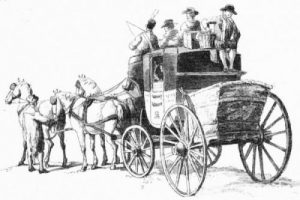

Whiskey Barrel Politics at Andrews Tavern

Close to the turnoff to Route 208 from Lawyer’s Road is a brick and frame building that a hundred and seventy years ago served as the site for politicking and whiskey sipping. Today, Andrews Tavern is a private home listed on both the Virginia and National landmarks registers. According to Mansfield’s Andrews Tavern History, in the 1840s it was the Whigs vs. the Democrats that brought the voters out to the polls with fife and drum parades, banners flying and dippers full of free whiskey for the all-day event. Wagon rides were available for those Tories and Democrats too intoxicated to make it home on their own.

Close to the turnoff to Route 208 from Lawyer’s Road is a brick and frame building that a hundred and seventy years ago served as the site for politicking and whiskey sipping. Today, Andrews Tavern is a private home listed on both the Virginia and National landmarks registers. According to Mansfield’s Andrews Tavern History, in the 1840s it was the Whigs vs. the Democrats that brought the voters out to the polls with fife and drum parades, banners flying and dippers full of free whiskey for the all-day event. Wagon rides were available for those Tories and Democrats too intoxicated to make it home on their own.

Samuel Andrews was the proprietor at the time, and no matter which party won he could make a profit on serving dinners to the poll-goers. Andrews Tavern was one of many watering holes located at convenient crossroads in the days of stage coaches, long dusty roads, and thirsty passengers. In addition to hospitality, “Andrews” also served as a store, a school, a post office, and a place to muster the local militia. Most of the food served at the tavern was grown on the adjacent plantation lands.

Spotsylvania Gold Rush

Spotsylvania is located in Virginia’s Gold-Pyrite belt and, from 1830-1849, our state was nation’s third leading gold producer. When the California gold rush hit, most interest in mining went west, but remains of the Goodwin Gold Mine can be toured on weekends from April to October at Lake Anna State Park. The scheduled, guided tour—available by reservation only--will allow you time to pan for gold. During its busiest period, there were more 20 working gold mines in the county and more were scattered through the region. Virginia’s last commercial gold mine closed in 1947.

Road to Ruin: The Civil War

Although no battles were fought in the immediate area surrounding Lawyers Road, the road itself was a valued thoroughfare for both armies. The plantations were largely deserted. Most able-bodied men had joined the army. At Andrews Tavern, Ella Samuel Andrews Cave waited out the war with her Uncle Samuel. Her husband, Lindsay Wallace Cave, had joined the 13th Virginia Infantry and would lose an eye at the Battle of the Crater in 1864.

In June of the same year, Union general Philip Sheridan and his cavalry rode west on Lawyers Road toward the Battle of Trevilian Station in neighboring Louisa County. According to Mansfield, with him were generals Torbett, Gregg, and Custer, four batteries of artillery, 125 supply wagons and 8,000 troops. They passed by Andrews Tavern on the morning of June 10, taking food and forage as well as money and jewelry, but they did not burn the buildings.

After the Battle of Trevilians on June 11 & 12, the Union army traveled back on Lawyers’ Road, this time eastward and accompanied by more than a thousand previously enslaved people. Confederate cavalry, headed by General Wade Hampton, followed on their heels on the dust-choked, broiling June day, when it is said that hundreds of the army’s horses perished under the extreme conditions, as described in a letter by Kate Kale written on June 13, 1864.

War Days and School Days at Bel-air

The years that followed the Civil War were hard ones for those who remained. One of those who stayed on at Bel-air was “Nannie” Scott, a great-granddaughter of Colonel Zachary Lewis. Zachary’s son Richmond (Nannie’s grandfather) had been a doctor during a time of few medical options. Dr. Lewis’s wife and all of his children eventually died from tuberculosis except for Sarah, Nannie’s mother.

Both Sarah and her sister Huldah were educated at their Uncle John Lewis’ school at Llangollen adjacent to Bel-air. They studied the classics and later married fellow classmates and brothers, James and Jason Scott. Huldah and her husband died a short time after they were married, leaving Sarah as the sole heir to Bel-air. Her letters revealed her sadness at so much loss of family and her reluctance to take on the duties of a plantation mistress, particularly the burden of enslaved people and the institution of slavery.

Sarah had twelve healthy children—six boys and six girls. Some of her sons attended the University of Virginia. Five of the boys served in the army, and the elder Scotts spent those years at Bel-air. Young Alden Scott left a record of his service in the Civil War that can be read online. Older brother Jim, home on leave, recalled hearing the guns from the Battle of Cedar Mountain, though the fighting was forty miles away. Jim Scott and two of his brothers would spend part of the war imprisoned at the notorious Point Lookout POW camp where he helped to look after the sick and injured. More than ten years after the war and encouraged by family and friends, he earned an official medical degree from the University of Virginia and settled in a nearby county.

After the war, most of the boys went further afield to grow their fortunes, with several settling in Texas, as there was little for them at home. In Reconstruction-era Virginia, land prices were at rock-bottom levels, and the war had destroyed many families’ savings, including the Scotts’. Before the war, the Scotts had managed seven plantations, but, as all the family’s gold had been willingly given to the Confederate government, the plantations had to be sold to clear the family’s debt—all except Bel-air.

The Scott sisters—Nannie, Millie, and Green—founded a classical school at Bel-air much like the one their great-uncle John Lewis had started decades ago. Nannie had taken her teacher examination at the University of Virginia, and Bel-air School opened its doors in 1894, following their parents’ deaths. The sisters took in local students as well as numerous nieces and nephews from their Texan brothers. While Nannie ran the school, Millie oversaw the boarding operation, including the farming that supplied the school with its meals. Their niece and teaching assistant Sadie Anderson recalled that Bible lessons were a foundation, and the students also delved into classical studies, Shakespeare, and folk tales.

The Scott sisters—Nannie, Millie, and Green—founded a classical school at Bel-air much like the one their great-uncle John Lewis had started decades ago. Nannie had taken her teacher examination at the University of Virginia, and Bel-air School opened its doors in 1894, following their parents’ deaths. The sisters took in local students as well as numerous nieces and nephews from their Texan brothers. While Nannie ran the school, Millie oversaw the boarding operation, including the farming that supplied the school with its meals. Their niece and teaching assistant Sadie Anderson recalled that Bible lessons were a foundation, and the students also delved into classical studies, Shakespeare, and folk tales.

The school’s students had a wonderful time, but within a few years, Bel-air School was in financial trouble, for the sisters had set the tuition and boarding fees too low to cover the cost and accepted students who could not pay. By 1901, the exhausted staff closed the school for a time. Nannie opened another school at Prospect Hill, but that, too, ran into financial trouble. Bel-air opened again in 1906, reduced in scope, but it closed permanently in 1910.

The sisters moved to Fredericksburg. Nannie and Green initially taught in public schools, but Nannie eventually left Fredericksburg to work for the federal government in Washington. She had still hoped to reopen Bel-air School, but soon died of cancer in 1914 while visiting her Texas relatives. Her sisters Millie and Green lived on in Fredericksburg until the 1930s. In 1935, film star Zachary Scott (grandson of Nannie’s brother Lewis) honeymooned at Bel-air, and he was also its one-time owner.

The Nuclear Age and Lake Anna State Park

In 1971, much of the old farmland on the western side of Lawyer’s Road was submerged when Lake Anna was created from North Anna River. The new lake, filled in partially by Hurricane Agnes’ leavings, was designed to serve as a water coolant for Dominion’s nuclear power plant. From 1972 to 1983, the area surrounding the lake was acquired and developed into a state park. Today, there are hiking trails that lead past the old gold mine, picnic areas, a swimming beach, cabins and campsites, and a fishing pond. Yet underneath the popular lake’s surface lies much submerged history.

Bibliography:

“Addison M. Lewis” in Virginia Baptist Ministers James Barnett Taylor. Philadelphia J.B. Lippincott c1859, 1859. pp. 474-475

Andrews Tavern History (1945) by J. Roger Mansfield.

Includes many old maps of the region as well as Andrews family history.

“Bradford Ripley Alden Scott: Memoirs of the Civil War”

(http://home.swbell.net/mck9/brascott/ - no longer viable)

“A Community for Learning: Spotsylvania’s Llangollen School for Boys…” in Fredericksburg, Virginia: Eclectic Histories for the Curious Reader by Ted Kamieniak.

“The Estate of John Marshall, Deceased…” CI: CR: SW: W. Wilson’s Admr. Vs. Hart. End year: 1811. CC: SW|W | 1809. ID: 576 – 53, Four papers; 16 exposures. Mentions payment due to Colonel Zachary Lewis for repairing a watch. Part of the Historic Court Records Project compiled by Barry McGhee

Dynamics of Lake Anna from McCotter’s Lake Anna Guide Service

http://mccotterslakeanna.com/lake.htm

Forgotten Companions: The First Settlers of Spotsylvania County and Fredericksburgh Town by Paula S. Felder. The American History Company, Fredericksburg, Va., 1982.

Gold in Virginia by Palmer C. Sweet

A Guide to the Zachary Lewis Account Book, 1762-1775

“Home School: More than 100 Years Ago, Three Sisters Founded Their Own School in Spotsylvania County,” by Barbara Crookshanks. Town & County section. Free Lance-Star, September 8, 2001, pp. 3-4. (pg 34 in Google view)

Genealogies of the Lewis and Kindred Families edited by John Meriwether McAllister, Mrs. Lura May Boulton Tandy (1906) pp. 134-147

Gentry and Common Folk: Political Culture on a Virginia Frontier, 1740-1789 by Albert H. Tillson. p. 25.

“The Indian Inhabitants of the Valley of Virginia." David I. Bushnell, Jr. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 34, No. 4 (Oct. 1926), pp. 295-298 (JSTOR)

“An Indian Vocabulary from Fort Christanna, 1716.” Edward P. Alexander. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 79, No. 3 (Jul. 1971), pp. 303-313 (JSTOR)

John Lewis (1784 -1858, son of Colonel Zachary Lewis)

http://www.ulib.niu.edu/badndp/lewis_john.html

Letters to Dr. James Carmichael & Son: Court Records

http://carmichael.lib.virginia.edu/collection/court/

Includes the names of elder Zachary Lewis’ enslaved people who had been lent to his daughter, Betty Lewis Littlepage Holloday. This dispute was continuing more than 50 years after his death.

*"Lewis Family of Warner Hall." The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 4 (Apr., 1901), pp. 259-265 (JSTOR)

“Living with War: A Local Boy’s Memories” by Barbara Crookshanks. Town & County section, Free Lance-Star, October 20, 2001. Pp. 4-6. Includes a photo of the Scott family in the 1850s and Bel-air.

Nannie Scott of "Bel-Air" School; the Story of a Woman Who, with the Help of Her Sister, Kept a School in the Nineties and Early Years of the Present Century by Nell Holladay Boand.

Virginia Gold-Resource Data by Palmer C. Sweet and David Trimble.

"Slave Owners Spotsylvania County, 1783 (Continued)"The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 4, No. 3 (Jan., 1897), pp. 292-299. JSTOR.

A Zachariah Lewis is listed as having 39 enslaved people in Spotsylvania.

Will of Zachary Lewis the Elder, 1764

http://carmichael.lib.virginia.edu/images/cr133053.jpg

Zachary, the son given the lands on the Pamunkey River as well as some lands in Culpeper County: “I give unto my son Zachary my negro man Morgan to him and his heirs.”

Items marked JSTOR are available to CRRL library card holders online at no cost.

The image of Colonel Zachary Lewis' powderhorn--used in the French and Indian War--appears on our site courtesy of the Virginia Historical Society.